An Old Ohio River Barge Boat Cook Brings a Musical Gift of a Lifetime to a Fledging Wheeling Musician named Griffith

She was a feisty old river woman who we called Aunt Ruth even though she was no relation. She spent years as a cook on barge boats that plied the Ohio River from Pittsburgh to ports in Kentucky and Illinois. When she returned from many of her sometimes-week-long river trips, she had the odd habit of bringing us chicken livers. One day, she also brought my brother, Terry, the offer of a special gift, but first, he would have to earn it in her family’s court of music.

Apparently, chicken livers were not so popular among the men who operated Ohio River barge boats. So, as Aunt Ruth prepared chickens to feed the men, she collected the livers in little plastic cottage cheese containers. Somehow, she had the impression that someone in our house would eat them. My Grandma always smiled politely and accepted the container before rushing into the kitchen to temporarily squirrel them away in the refrigerator. On one visit, Aunt Ruth heard Terry strumming away on a little learner guitar.

“Terry, that little tinker toy ain’t nuthin,” she said in a voice that sounded like Marjorie Main, who played Ma in the old Ma and Pa Kettle movies of the 1940s. “I got a real guitar that’s been in the family a long time. You come up to the house next weekend and maybe we can see if it fits you. Now it ain’t much so don’t get too excited. No one has played it since cousin Jimmy back during the war. But, there’s no sense in it gathering dust if you think you can put it to use. But, we will have to see.”

Not long before this productive little visit from Aunt Ruth, Terry had decided to transition from his first musical instrument – the marimba – to the guitar. The reason for the switch was his growing interest in the folk music phenomena that was sweeping the country and his determination to use his voice as well as his hands to make music. As always, our blind Grandma played a key role in the transition by financing a new very cheap little learner guitar.

It was 1963. I was nine. Terry was 16. We were being raised in Elm Grove by two widows, our Mother, Mabel, and our Grandma, Lizzie. We were one of those many families who didn’t have much disposable income, but, thanks to sound financial management by Mon and Grandma, Terry and I never realized it. Our Great Depression-seasoned elders knew how to pinch a penny as well as how and when to splurge.

We never had a fancy high fi or record player. Instead, we had a U.S. Library of Congress-issued “talking book.” That’s what the government called the compact rugged little mono speaker record player they gave free to blind people so they could subscribe to books and periodicals on vinyl records. Grandma was, frankly, too busy to listen to it. So, she let us keep it in the bedroom we shared on the second floor of our little Columbia Avenue Cape Cod. That’s where I was awakened every morning to the static-infused flat-sounding strumming and harmonies of the Kingston Trio and Peter, Paul, and Mary and fell off to sleep every night to Bob Dylan and Phil Ochs. I kind of absorbed the music through various states of sleep. But, Terry was ingesting it with all his attention. He wasn’t just listening, he was figuring out how to play it himself.

He had been pecking away at the beginner’s guitar and was becoming quite proficient, all without lessons. Before long, instead of the Kingston Trio, I was hearing Terry sing “scotch and soda… jigger o gin…oh what a spell you got me in…oh me oh my” as I fell off to sleep clutching my stuffed animal du jour.

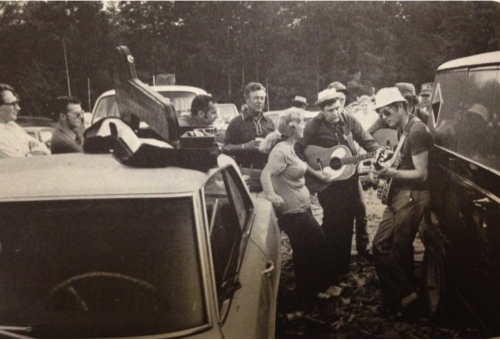

The weekend after Aunt Ruth’s most recent chicken liver delivery, we piled in the old Rambler and Mom drove us up Stone Church Road to Aunt Ruth’s house someplace in the country. It was a hot afternoon. When we arrived, a dozen or so of Aunt Ruth’s relatives were relaxing on the grass and in lawn chairs under the shade of big old oak trees. They were laughing, talking and sipping ice teas. Not long after we settled in with them, a group of men came out of the small little house nearby carrying guitars, a banjo and a mandolin.

“Did you bring your little tinker toy?” Aunt Ruth asked Terry. “Good. Get it out and sit down there next to my boy Bobby. Just join in.”

This was not, by any means, one of those big bluegrass jam sessions you sometimes see in the movies. There was way more strumming than picking and the music they played were plain old country standards. Friends and family joined in to sing “Let Me Call You Sweethart,” “You Are my Sunshine,” and “The West Virginia Hills.” Terry, his eyes glued to the left hand of the man named Bobby who played a beat-up old guitar, strummed along and duplicated the simple cords he saw the others play.

After an hour or so, Bobby, who was no boy but rather an old man who must have been his 30s, clapped Terry on the back as a kind of gesture of approval.

“Let’s take a little walk inside,” Bobby said. “It’s Terry right? You done just fine Terry.”

Inside, Terry watched Bobby walk to a door that he assumed was a hall closet. His host opened the door, bent over and disappeared into cavernous blackness. Soon, he heard Bobby muttering to himself and saw books, boxes, old articles of clothing, tennis rackets and dozens of other objects come flying out of darkness.

A full three minutes later, Bobby arose out of the storage nightmare with a smile on his face and a worn old guitar in his hand. He held it out to his young guest.

“Here you go young man,” he said. “Sorry there’s no case.”

Terry took the old instrument and ran his hand over the smooth old mahogany finish swiping away a decade or so of dust in the process. It was a 1937 Martin R-18 archtop. It had steel strings and two big “F” holes like those found on violins instead of the more common one big round sound hole. Its neck was discolored from frequent use and the wood between the frets was burrowed and uneven from years of work.

There was no backstory provided about the guitar or how it found its way into the storage closet. All we knew was that it belonged to some guy in Aunty Ruth’s family who played it during World War II and apparently abandoned it with her.

It had a great deal of character and, after a long tuning and adjusting period, it produced a mellow sound that was as smooth as honey. Terry was in love at first sight.

The old Martin became his constant companion. It went to school, to friends’ houses, on our family trips to Buckhannon and Romney—anywhere where Terry could play it. He learned more and more songs, like “If I Had a Hammer,” “Blowin in the Wind,” “Tom Dooley,” and “Where Have all the Flowers Gone.” He honed his vocal skills with voice lessons and gained polish and experience by performing complex solos in the church choir. By 1964, he formed his own little folk group called the Columbia Singers with fellow Triadelphia High Schoolers Tam Mallory and Bill Lang. Lang and Mallory were a year older and when they graduated, Jan Worthington and Eric Ackerman stepped in. The tough little Martin played on.

His senior year at Triadelphia in June 1965, Terry agreed to provide guitar accompaniment to a girl who sang “Michael Rowed the Boat Ashore” for the senior talent show in addition to performing with his trio. The show was a big success. Even I was impressed as I sat on those hard-wooden fold-up auditorium seats where someday I would suffer through biology lectures and pep rallies during my own high school career. Everyone was invited back to our house for snacks and a post-show mixer.

Terry was late arriving. He had a separate ride and we were already home in the little house’s living room with several of his classmates awaiting his arrival. The doors and windows were open to fight off the early summer heat. We heard a car pull up, a car door slam, and then a horrible crushing splintering sound before a period of silence.

When Terry opened the wooden screen door and walked inside muttering obscenities for the very first time in front of our Mom, he sadly held out the old Martin. Its sides were shattered into dozens of pieces. There was an audible gasp in the room. Terry, explained that in his haste to join the party, he forgot all about the tree stump in front of the next-door neighbor’s house where his ride had let him out of the vehicle. He tripped, fell on the guitar hitting the sidewalk, and smashed it.

The party never really got going after that. The people dispersed early, Mom and Grandma cleaned up and I went off to bed. As I lay in my hot dark bedroom I could hear my brother through the open window as he sat on our rusty yellow metal glider in the darkened back yard. He picked and strummed a slow mournful song on the old wounded Martin that I couldn’t quite make out. It’s honey smooth sound was now a rattling tinny noise. Mom said later it was like Terry was having a funeral for an old friend.

We kept the Martin in the basement for a couple of years where it gathered dust. Eventually, Terry found a man in Elm Terrace who could restore it. He had it in his workshop for many months. When it came back, it was whole, but there were mismatched pieces of wood in it that replaced parts that were lost in the accident. The Martin just never played or sounded good again. Eventually, Terry put it in a cheap case and stored it away.

The night before he left for the Army in 1971, Terry gave me the Martin in the hopes that I might learn to play on it, but mostly as a keepsake amid the uncertainty of the times. I never learned how to play guitar, but I kept the Martin for the next 35 years before giving it to a friend who collected and displayed old instruments. It seemed a worthier fate for an old friend than banishment to basement storage rooms.

The old Martin was just old wood and strings, but it brought much pleasure and left its mark on the people who played it and the people who heard it sing.