“Cozy, isn’t it?”

“Cozy?!… A good fart would give you a concussion!”

That hilarious exchange came from none other than Walter Matthau’s and Jack Lemmon’s characters in the 1997 movie Out to Sea upon entering their tiny cruise ship cabin and realizing they would be crammed into it for a week-long trip. Be it hotel rooms, cruise ship cabins, dorm rooms, or small apartments – many of us can relate when we consider the small spaces we’ve found ourselves in, although, perhaps not quite in those colorful of terms.

In recent years “tiny living” has become a popular trend in the United States and challenges the modern norms of housing. Economic downturns and uncertainties over the past decade have given way to the idea of living in smaller, more affordable spaces with an emphasis on reducing or eliminating as many short and long-term costs as possible while also being eco-friendly. However, the idea is not a new one. In fact, this type of lifestyle, now back by popular demand, has origins right here in the Ohio Valley.

Most notably, famed artist Harlan Hubbard not only experienced and enjoyed both shantyboat and tiny living, but also highlighted that simple way of life in his writings while living at Payne Hollow along the Ohio River in Kentucky.

The Boat Stops Here

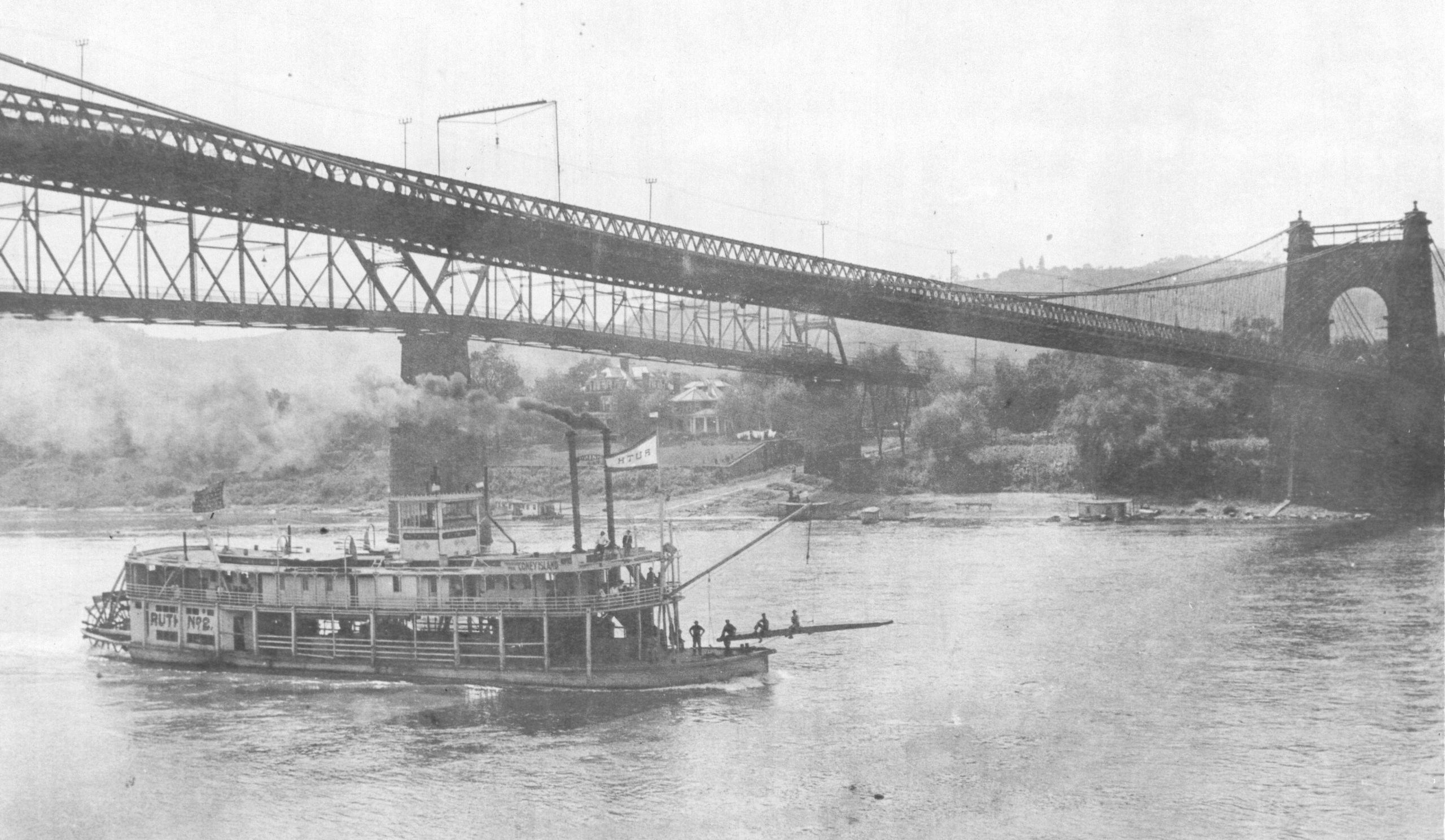

Before the days of HGTV, tiny house living wasn’t as appealing or as stylish. From the late 1800s to the 1940s, the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers were home to thousands of working poor families living on floating houseboats known as shantyboats. Built of wood and any other materials acquired or salvaged, these small crafts were the original tiny houses and drifted from place to place, having no engines or means of propulsion. Their appearance along the banks of many a river town, including Wheeling, were directly tied to the boom and bust economic cycles that are well noted in our nation’s history.

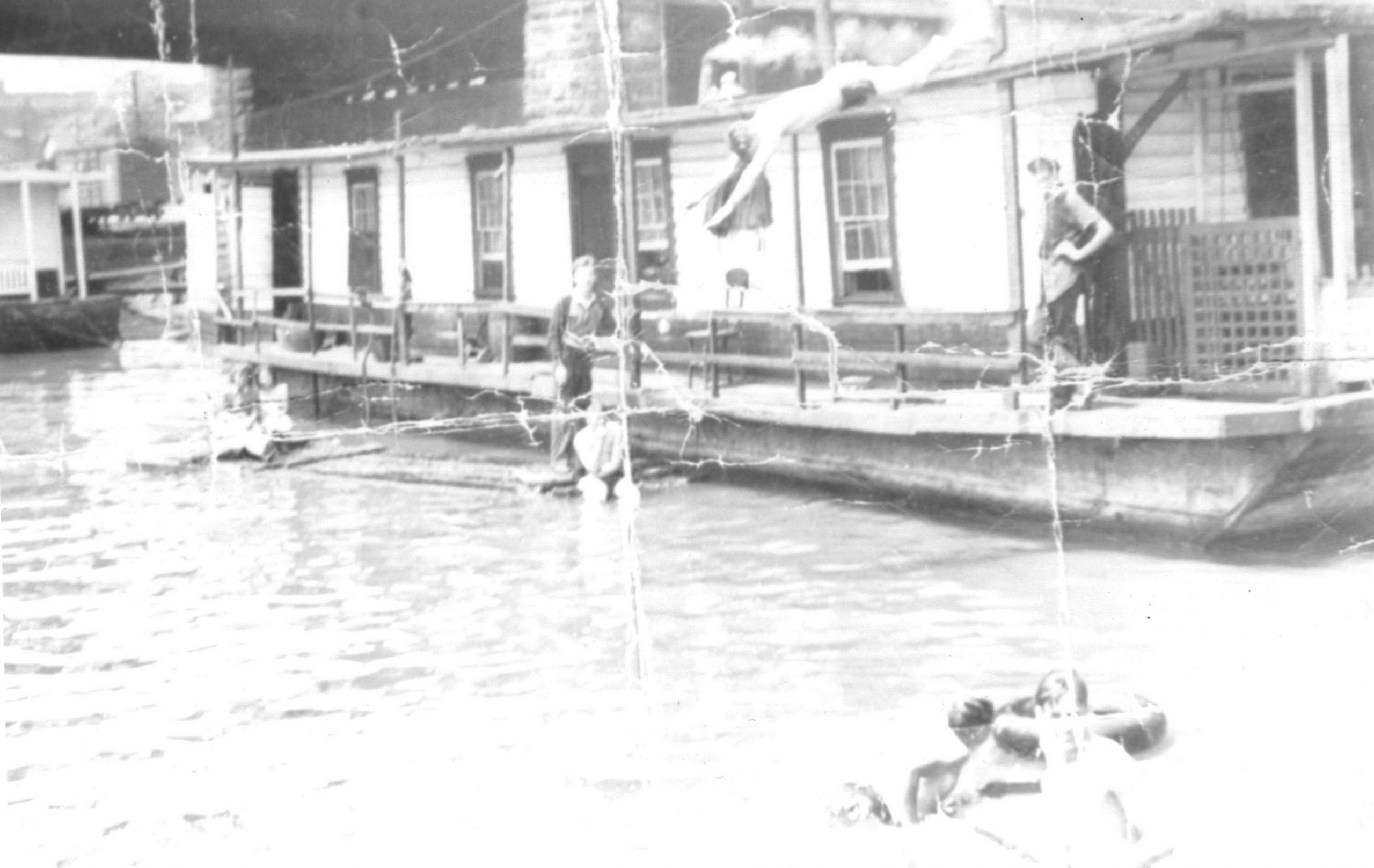

Many river towns initially had no choice but to permit such boats along its shorelines, but over time ordinances were passed in some cities banning the boats from cluttering their waterfronts. Oftentimes, shantyboat inhabitants were unfairly labeled as stereotypical drunkards, do-nothings, and riffraff. In reality, however, more than half of shantyboat occupants were women and children. While Wheeling may well have passed ordinances of its own, photographic evidence of shantyboats along Wheeling’s waterfront suggests otherwise or perhaps one that was loosely enforced.

During the Second Industrial Revolution, Wheeling saw significant development from steel and other manufacturing industries. Coal mining, railway construction, factories, and other expansions brought about some of the fastest growth the city had seen.

Unsurprisingly, however, that growth did not translate into growing wages and better living conditions. Like their English counterparts, the working-class of Wheeling and the United States were predominantly unskilled laborers subjected to 12-16 hour shifts daily at barely a living wage while enduring harsh and unsanitary working conditions throughout the late 19th and into the early 20th century.

While some were financially able to own what we would deem a respectable home, many others were not able to afford to buy a home or pay property taxes and resorted to shantyboat living. Drifting from town to town, life was truly lived one day at a time. Ultimately, home was wherever a job could be secured and the boat could be tied up.

The Original Tiny Living

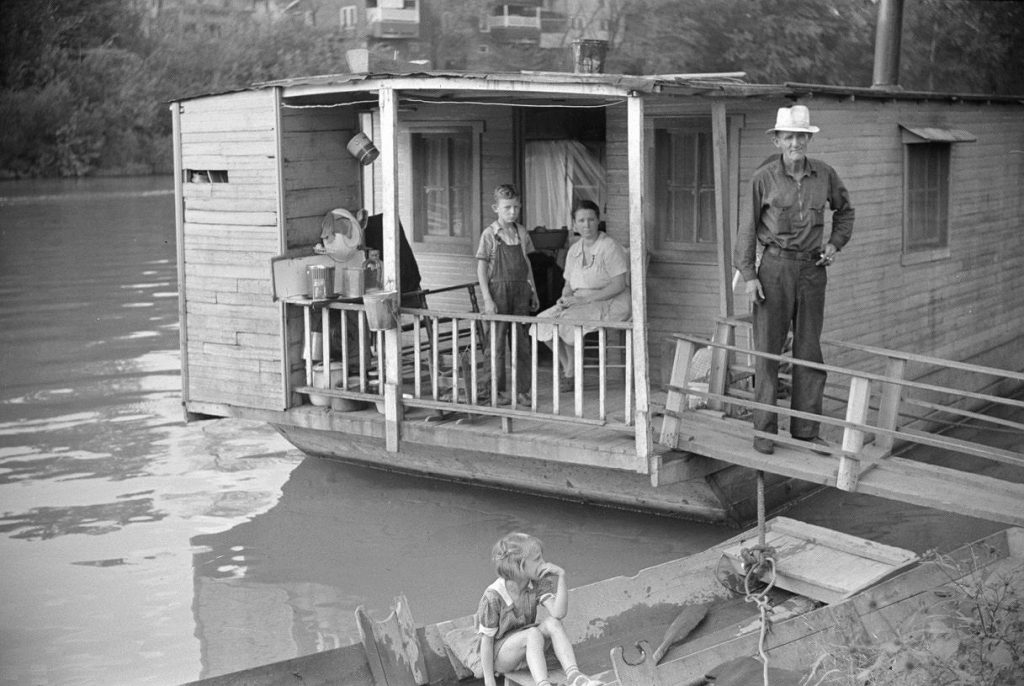

The typical shantyboat was constructed on a long, narrow wooden hull approximately 20 to 40 feet in length and 10 to 12 feet wide. Out of all of the components of the boat, the hull was the most important and built using white oak or fir to provide maximum strength and durability. The superstructure or cabin portion of the boat, much like today’s tiny homes, was primarily a one-room affair encapsulating kitchen, living room, and bedroom for the entire family. However, some more spacious boats could have multiple rooms that gave the place a more traditional home-like atmosphere. What we would consider a “base model” shantyboat would cost about $50 to build, while a larger and more aesthetically pleasing boat could run as high as $200-$300 to construct.

You might be thinking these boats had to be drab eyesores lacking any character, and in some cases, you would be correct. Just as it is today, not all people in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were skilled or creative. Yet, many of these boats were built with the same pride and attention to detail found on homes of the period with no two shantyboats being alike. Clapboard siding, functioning shutters, porches on the bow and stern, and even ornate gingerbread trim work were not uncommon elements. A narrow plank, known on the river as a stage, connected the boat to shore allowing egress throughout the day and was usually hauled in at night to prevent any unwanted visitors.

From within, a shantyboat was fairly spartan in décor and in amenities. Electricity was nonexistent and drinking water was carried to the boat from nearby springs or water sources. Curtains were oftentimes made of scrap fabric by the wife or an older daughter who was assisting with the daily household chores while one or both parents were working. Rugs were home-woven if the proper materials could be found or vinyl floor cloths similar to linoleum were brightly painted to resemble tiled floors or floral carpets.

Formal education was next to nonexistent, the extent of which consisted of a mother or an elder sibling teaching the younger children basic chores and, if lucky, how to read and write. More often than not, however, children were selling whatever goods they could on the streets to help the family.

Bathing was a matter of choice, not of necessity. However, if one took to the urge, they needed not look any further than outside their window at the vast river around them. Depending on the size of the boat, a small water closet (toilet) was sometimes built on the corner of one of the porches or inside the boat that allowed for privacy – and a “flushless” exit directly into the river. If one was not privy to such a “privy”, their next best option was a ceramic chamber pot that was rinsed after each use.

Just as we see in today’s tiny living, storage and maximization of space was utilized to the fullest such as folding tables and counters mounted to the walls, shelving, and built-in storage cabinets for canned and dry goods. Only those few possessions that were owned along with daily necessities could be fitted in most shantyboats. Laundry was typically done using metal wash pans and washboards then hung out to dry on lines stretched across the boat’s porches. If it was cold, they would be hung inside near the stove for maximum drying effect.

In warmer months, windows and doors were left open to allow cooler river air to circulate through while in colder months the boat was shuttered up tight and kept warm by iron pot belly stoves fueled by kindling or, if they were lucky, by coal found along railways that had fallen off passing railcars. Kerosene lanterns and homemade wax candles provided light in the evenings.

On shore, some shantyboat dwellers maintained gardens on the nearby shoreline and kept chickens and other fowl in pens, sometimes on the roof of the boat, for fresh eggs and meat. Even if those sources were not possible, the river’s ample supply of fish or occasional trips to the market could provide the family with quite an ample spread.

And if running a floating household wasn’t arduous enough, maintaining the boat’s buoyancy and monitoring a rising river presented challenges of its own, not the least of which was the danger of losing your home. While many boats could ride out a flood thanks to experienced owners, others found themselves and their boats high and dry after the high waters receded thus beaching them ashore. This scenario, while not all that uncommon, resulted in shantyboat owners taking up residency on land until the next flood, or at least they hoped, lest they get an unfriendly landowner who wanted them and their boat off their property.

Living in such a manner was certainly unconventional but make no mistake, however, in many cases, those who lived on shantyboats found enjoyment in their lifestyle at minimal expense.

A Relic of the Past

The days of the shantyboat along the shores of Wheeling and the Ohio were not to last forever, but their run spanned two different centuries and lasted over 50 years. The 1891 Marietta Register proclaimed, “Over 8,000 families live in shanty boats along the Ohio River, and float from town to town, feeling as happy as if they owned the earth.” Yet, in later years that number is believed to have been even higher as an estimated 50,000 Americans called shantyboats home.

By the time World War I drew to a close, the United States had already enacted the federal income tax and a dramatic shift in living conditions began to take hold as working-class living conditions and wages improved following the organization of unions and other collective bargaining groups.

A steady decline of shantyboat living continued until the Great Depression once again forced thousands of families out of their homes. According to Mark Wetherington, who is a senior research fellow at Louisville’s Filson Historical Society, “The actual peak time for shantyboats (they were beginning to trail off in the Post World War II period) was the Great Depression.” By the early 1930s, shantyboats saw a resurgence among poor and working-class families. It was only after President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs took hold and began bringing the country out of the dark days of the Depression that the last of the shantyboats began to fade into history.

Incredibly, out of the thousands of shantyboats that existed, only one known example remains and is on display locally in Marietta, Ohio.

The story of this fascinating time capsule came to light eight years ago when the Schoonover family of Gallipolis, Ohio contacted the Sons and Daughters of Pioneer Rivermen (known as S&D) about donating the vessel. In 1963 the family purchased property along the Muskingum River above Marietta where the shantyboat, which was reportedly beached on the bank during the massive 1936 flood, was used as a makeshift cabin and camp.

“It was built between 1910 and the early 1920s by someone who really knew what they were doing. When S&D acquired the boat, it needed a new roof and the flooring had been removed to transport the vessel then put back in place, but overall it was structurally sound,” said Jeff Spear, who is president of S&D.

The boat itself was in relatively good condition considering its history and age. Most of the furnishings within were original to the vessel and provided insight into how families managed to live in such cramped but cozy conditions. Spear and other volunteers helped prepare the vessel for its short journey from Beverly, Ohio to the grounds of the Ohio River Museum in Marietta. However, it was no easy task. Its location over an embankment required a delicate hauling-out process and a massive yellow jacket nest located somewhere within or around the boat set all present to flight until the swarm could be exterminated.

Once on-site at the museum, the vessel was repaired and restored as a stationary outdoor exhibit. Visitors today can enjoy the interactive exhibit and fully experience shantyboat living.

History Repeats Itself

As our nation and world face economic uncertainties, shantyboat living and its successor, tiny living, take on more relevance today as people look to preserve resources and money. We are reminded that the same issues that forced people to abandon their homes or give up hope on ever owning one less than a century ago are once again being experienced today.

And if history is any indicator, we should be likewise reminded that we will emerge from this economic downturn just as we did after the Great Depression and the Great Recession a decade ago – the results of which I hope will make tiny living predominantly a choice of preference rather than one of necessity.

• Taylor Abbott is the treasurer of Monroe County, Ohio, and was born in Wheeling, West Virginia. He is a graduate of Ohio University and is co-founder and president of the Ohio Valley River Museum. He serves on the board directors for the Sons & Daughters of Pioneer Rivermen and is an advisor to the Ohio River Museum in Marietta, Ohio. He enjoys hiking, travel, historic preservation and restoration work. Taylor resides in Clarington, Ohio, with his wife Alexandra in a former church they purchased in 2016 and renovated into their home.