April 1865, was a month long remembered in history. Richmond, Virginia, fell; April 9, Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered to Gen. U.S. Grant; April 15, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated; April 26, John Wilkes Booth was killed; and on April 27, the Steamboat Sultana — with Wheeling soldiers on board — exploded.

The country was grieving and war-weary — none more so than prisoners of war. Prisoners, and especially those at Andersonville, Georgia, had endured an open-to-the-weather stockade, rampant disease, lack of nourishment, unsanitary conditions and lack of medical treatment. At last, the war was coming to an end, and opposing armies agreed to release their prisoners. The paroled soldiers left Andersonville on March 18, 1865, traveling north by train, boat and on foot, finally arriving at Camp Fisk Mississippi to await the last leg of their journey home. What a celebration they had when they reached the “Big Black River” that separated the Union and Confederate troops. For many, it was their first glimpse of the American Flag! Soldiers were issued new clothes and provided real food. Also helping was the U. S. Sanitary Commission, an organization founded by civilians to assist the army in providing care and personal Items for the soldiers. There were some 5,000 soldiers at Camp Fisk. More than 1,000 of the former Andersonville prisoners were ill.

HEADING HOME?

At last, word came to leave Camp Fisk, take a short train ride to Vicksburg, Mississippi, then home. Approximately 2,200 people boarded the steamboat Sultana, a boat designed to carry 376 passengers and crew. The Sultana left Vicksburg April 24 — at last, the jubilant paroled Union prisoners were on their way home, or so they thought.

The Sultana made its way upriver to Memphis, Tennessee, arriving April 26. There it unloaded 120 tons of sugar, and then crossed the river to take on fuel. The next scheduled stop would be Cairo, Illinois, from which many planned to travel overland to Camp Chase and then home.

The Sultana was fighting its way north against a raging Mississippi River flooded from the spring-snow runoff. The river had spread over a great distance and, in the darkness, it was impossible to see either side of the Mississippi.

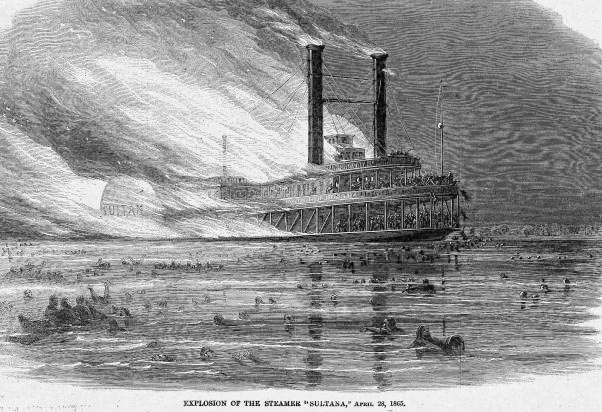

At approximately 2 a.m., without any warning, the boilers on the boat exploded, sending a deadly spray of scalding water, steam and pieces of red-hot iron through the heart of the boat. Support structures for the main and cabin decks shattered. When an emergency occurred on the rivers, the pilot’s duty was to guide the boat into the bank. Unfortunately the explosion had torn the pilot house in half, and no one was alive to help. The Sultana became adrift and soon was an immense ball of fire, floating down the river and lighting the sky for miles.

The Mississippi was filled with hundreds of frantic drowning people and dead bodies. People clung to shutters, steps, boards, logs, even dead horses and mules, anything that would float.

At 3:15 a.m. the Steamboat Bostona II, heading for Memphis, rounded a bend and saw the flames. A private, Wesley Lee from Ohio, floated down the river to Memphis and sounded the alarm. A few minutes later, other boats were on their way and began to rescue men, women and children. All along the river, many people, including a young man wearing a Confederate jacket, did their best to help.

As soon as Lt. Col. B.T.D. Irwin, the medical director and superintendent of the government hospitals in Memphis, was informed of the disaster, he immediately ordered ambulances and medical attendants to the wharf and joined in the treatment of victims. The church bells began ringing, and the citizens of Memphis quickly responded to the needs of the survivors.

Memphis had been captured by Federal forces in 1862, and due to its position on the Mississippi River and its rail depot, it was the ideal location for military hospitals. Memphis became a supply and recuperation city with numerous hospitals, trained personnel and the latest medical equipment. By war’s end, more than 5,000 wounded and sick soldiers had been treated there.

The citizens of Memphis woke to a chaotic scene — bodies of the dead lined up on the wharf, and survivors, who reached the waterfront black from smoke, burned, scalded, wounded and dying. Members of the U.S. Sanitary Commission were the first on the scene along with the Sisters of Charity, lay volunteers of the U. S. Christian Commission. (When the Sultana had left Memphis, there had been no doctor on board to care for them. Twelve Sisters of Charity volunteered to take passage on the Sultana to care for the sick and wounded soldiers. Only one member was known to have survived).

These noble volunteers washed the blackened victims, and gave them red flannel drawers, shirts, food and coffee. As quickly as possible, horse-and-mule driven ambulances took the seriously wounded up the steep bank of the Memphis waterfront to the hospitals. Record keeping on the Sultana was disorganized, and the exact number of persons on board was hard to compile. The Sultana Museum in Marion, Arkansas, estimates that 1,700 to 1,800 perished.

TRAGEDY HITS HOME

Below are the known Wheeling soldiers who were on the Sultana, along with two from Ohio who became Wheeling residents:

• William Cruddas was captured at Lynchburg, Virginia, on July 28, 1864. A newspaper article from the Memphis Argus, April 28, 1865, by Sgt. L.B. Hinckley states: Among those found by (John) Fogleman picked up from a nearby steamboat landing was Pvt. William Cruddas (1st West Virginia Cavalry) while almost In the agonies of death. Cruddas was holding to the limb of a partially submerged tree with such force that Fogleman had to cut the limb before he could get Cruddas onto the raft. Fogleman carried the soldier to his house, but Cruddas died before he could be transferred to a Memphis Hospital.

In addition to the kindness and heroism of the people of Memphis they also provided burials for a great number of unknown soldiers. Cruddas is one of the few buried in the Memphis National Cemetery with his name on his grave marker. The majority of the grave markers in the cemetery say Unknown. Cruddas had the foresight to pin his name to his uniform. (In 1906 identification tags were made mandatory).

• Henry Foster served in the First West Virginia Infantry. The account of Foster’s capture is given by Henry Maze: That on or about the 15th day of May, 1864, while in the line of duty, and without fault or improper conduct on his part, at or near New Market, State of Virginia, the claimant was captured by the Rebels in the Battle of New Market, while assisting to carry me to a farm house. I having received a gunshot wound in left leg. After hours in the Mississippi, Foster was rescued clinging to the top of a tree. He returned to Wheeling and is buried at Mount Wood Cemetery, Wheeling. (Foster’s brother John, also served in the First West Virginia Infantry).

• Alexander Manners, First West Virginia Infantry, was taken prisoner May 15, 1864, at New Market, Virginia. At the same battle, Alexander’s brother, Martin Van Buren Manners, the driver of the lead team of horses for Carlin’s Battery, was shot and killed. Alexander perished when the Sultana exploded. He is either buried at the Memphis National Cemetery with the marker, Unknown Soldier, or he was lost to the Mississippi River. (Their brother, Joseph Manners, who survived the war, was also a member of Carlin’s Battery).

• Theophilus W. Richardson served with the First West Virginia Infantry. Captain William Robb gave an account of Richardson’s capture: On the evening of 30th Jan. 1864, Cpl. Theophilas Richardson, with two others were detailed to make a scout towards Moorefield and during their absence the Brigade was ordered to retreat to New Creek during the night by a road flanking Gen. Rosser’s command. Next morning Gen. Early & Gen. Rosser moved forward to attack Petersburg, capturing a number of our men on the morning January 31, 1864. Cpl. Richardson and Adam Radar was captured while assisting Capt. O’Rourke, his horse having fallen with him and broken his (Capt. O’Rourke’s) collarbone all which I know personally having been captured same morning myself and was taken to Richmond together. Richardson escaped and waded across the river at Moorefield, West Virginia. He was captured and sent to Belle Isle Prison and then removed to Andersonville Prison. Richardson stated that he had escaped from Andersonville, Nov. 28, 1864. He somehow was on the Sultana and was taken to the Soldiers’ Home in Memphis. Richardson died nine years later and is buried at Sardis, Ohio.

• Anthony Craig was one of the “older” men to immediately enlist in the army. He was first mustered into the Infantry and later joined Carlin’s Battery in February 1864 only to be captured at Mason’s Creek June 1864. He was presumed to be held prisoner at Andersonville. Craig drowned in the Mississippi when the Sultana exploded. (Anthony Craig was born in Ireland as was his son, Captain John Craig, who served in the First West Virginia Infantry).

• James McKendry, born in County Down, Ireland, was a blacksmith and toolmaker, probably from Pittsburgh. He served in the Wheeling-based infantry and artillery. In 1863, surrounded by the enemy, orders were given to destroy the caissons to prevent their capture. A full caisson of ammunition exploded and hurled McKendry against a tree. He was hospitalized for four months. McKendry’s service record listed him as having deserted. The unfortunate truth — he was captured at Hunter’s Raid at Lynchburg and sent to Andersonville Prison. After the Sultana exploded, he spent hours in the freezing Mississippi with multiple injuries. He was rescued and taken to Washington Hospital in Memphis. His next stop was Camp Chase, Ohio, where he was hospitalized for six weeks. McKendry moved to Chicago and was known to be living at Cottage 7, Illinois Soldiers’ & Sailors’ Home, Quincy, Illinois.

• George C. Loy enlisted in Carlin’s Battery. Loy became an expert on Confederate prisons. First captured June 1863, he was temporarily imprisoned at an old tobacco works in Richmond and then Belle Island Prison. Armies were still making prisoner exchanges at that time, and he was soon released. On May 21, 1864, he was captured and sent to the worst of the worst prisons — Andersonville. Loy’s adventures continued as he headed home on the Sultana. When the explosion occurred, Loy jumped into the icy, flooding Mississippi. He waited hours to be rescued and was then taken unconscious to Washington Hospital, Memphis. Loy died at the age of 35 and is buried at Mount Wood Cemetery.

• George Smith first served in the First Infantry driving a team of horses. He became ill and, when recovered, enlisted in Carlin’s Battery. On a line march from Lynchburg, Virginia, June 21, 1864, he was captured and sent to Andersonville Prison where he suffered from scurvy and diarrhea. Smith, when the Sultana exploded, suffered a skull fracture. After spending several hours in the Mississippi, River, he was sent to a hospital and then transferred to the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Home in Memphis. At the time of Smith’s death, he was living at the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Home in Adams County, Illinois as was his brother, Thomas B. Smith, of the Fifth West Virginia Cavalry. George Smith is buried at Woodland Cemetery, Quincy, Illinois.

• Allen Stephens was 19 years old when he enlisted in the First (West) Virginia Light Infantry. After his first-three month enlistment was completed, he joined Carlin’s Battery. He was taken prisoner June 14, 1863, at the battle of Winchester where he was shot in the foot. Stephens was in and out of hospitals for a good while. On June 21, 1864, he was captured at Mason’s Creek and sent to Andersonville. Stephens perished in the Sultana Disaster. Stephens’ family erected a beautiful Cenotaph at Mt. Zion Cemetery, Wheeling in his memory. Mt. Zion Cemetery volunteers are to be commended for their great effort in the preservation and loving attention given to the cemetery and Cenotaph). Stephen’s older brother, Professor Samul Kyle Stephens, lived in Indiana and was one of the first to volunteer. Kyle was commissioned first Lieutenant of Company G, Seventh Indiana Volunteers, commanded by Col. E. Dumont, and served with distinction in McClellan’s campaign in West Virginia. Brother Benjamin volunteered in a Pennsylvania regiment and sister, Amanda Stephens Murdock, organized the Provisional Department of the Women’s Relief Corps of West Virginia and was later named its president.

• Thomas Moore and DeMarquis Lafayette (Lafe) Githens served with the 50th Ohio Infantry. Thanks to Thea and John Gompers sharing family letters from Moore (John’s family), we have learned that Thomas Moore was a Sultana survivor as was Lafe Githens. Both men were captured at the Battle of Franklin, Tennessee, and imprisoned at Cahaba, Alabama. After the war, they settled in Wheeling where they spent the remainder of their lives. Moore lived at 53 South Huron St. and operated the grocery store on Wheeling Island at the corner of South York and Virginia streets. Githens died at his home at 950 ½ Market St. when he was 92 years old. Moore’s family received a letter from Washington Hospital, Memphis, written by a member of the Christian Commission. Moore’s hands were scalded and his feet burned from walking on the burning coals of the Sultana. Githens’ obituary stated he had been on the upper deck near the pilot’s house, and his leg was badly scalded when the explosion occurred. He seized a window shutter and leaped into the water, floating to a small Island where he was rescued by the steamboat Silver Slipper and taken to Overton Hospital, Memphis. Thomas Moore is buried at River View Cemetery, Martins Ferry, Ohio, and Lafe Githens at Greenwood Cemetery, Wheeling, West Virginia.

• Zachariah Taylor Woodyard was only 16 when he enlisted with the 4th West Virginia Cavalry. Woodyard was almost captured immediately and sent to Libby Prison, Belle Isle Prison, and Andersonville. In Andersonville, he contacted scurvy and rheumatism. The kindness of a former baker from Wheeling, Confederate James Duncan, probably saved his life along with other prisoners from Wheeling, by giving them work outside the stockade in the bake house. The extra food made all the difference in their survival. Duncan was later accused of a murder, despite the fact that the victim was never found. Woodyard and other Andersonville prisoners and concerned Wheeling citizens testified at his trial. He was convicted but later escaped from prison. Woodyard is buried at Fairview Cemetery, Wirt County, West Virginia.

The information in this article was from the book, On the Way Home, by Linda Cunningham Fluharty, that tells the story of all the West Virginia soldiers on the Sultana, and Fluharty’s and Edward L. Phillips’ book, Carlin’s Wheeling Battery, a History of Battery “D” First West Virginia Light Artillery. An unbelievable amount of their research and hard work have provided an encyclopedia of historical information and enjoyable reading. Addition information and assistance were given by Margaret Brennan, Jeanne Finstein and Dr. Louis Intres, Sultana Disaster Museum, Marion, Arkansas.