At Weelunk, we’re all about keeping you connected to your community. Because that looks a little different right now, we’re bringing you ways to engage while staying safe and healthy. We hope Weelunk can continue to connect you to Wheeling — no matter where you are.

In the decades before online banking and electronic payroll deposits became the norm, vaults or “strong rooms” were once commonly constructed in banks, businesses and homes. Typically made of concrete reinforced with steel, these strong rooms were meant to withstand burglars, natural disasters and even the occasional angry mob.

As Wheeling grew as an industrial center in the late 1800s and early 1900s, businesses and prominent families in town began utilizing vaults to secure their monies, important records and prized possessions from real or perceived threats.

The vaults were integral parts of the buildings which housed them. And many of these vaults still remain, with stories to tell.

WEST VIRGINIA INDEPENDENCE HALL, 1528 MARKET ST.

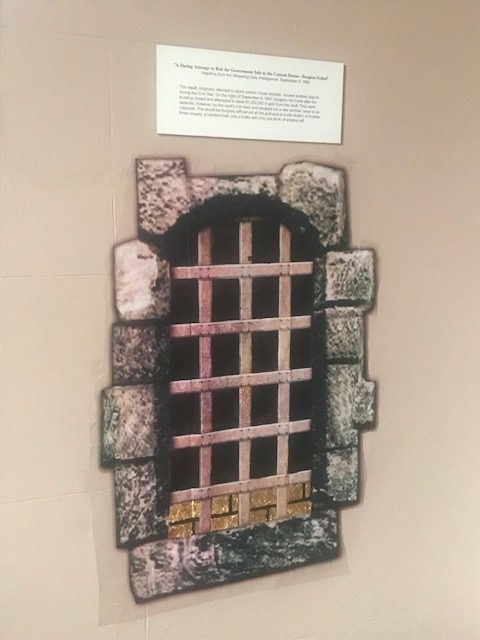

Where there were vaults, there are bound to be those who would like to steal what’s protected within them. The vault on the second floor of West Virginia Independence Hall (WVIH) is one that has withstood at least one attempt to access its contents.

In September 1862, West Virginia was still nine months from its secession from Virginia. The city of Wheeling, having been claimed by Ebenezer, Jonathan and Silas Zane in 1769, was now a transportation hub nestled on the banks of the Ohio River. The now-historic Suspension Bridge had been funneling people and goods westward over that river for over a decade. During this time, Wheeling was the 63rd largest city in the nation and was serving as the capital of the pro-Union Restored Government of Virginia, which played a pivotal role in the creation of the state of West Virginia.

Known in those times as the United States Custom House, WVIH was a bustling center of government activity. In addition to the customhouse that was kept busy with shipments coming and going from the river wharf, the building also housed a post office, the governor’s office and federal district court.

Deborah Jones, WVIH manager, tells Weelunk that as a building with so many important functions, the Custom House would have had stockpiles of ammunition and supplies for the local troops on hand inside the building. Also, great sums of gold were kept in the vault that was located in the Inspector of Customs’ office on the second floor. This gold would have been used to pay soldiers, buy supplies, meet payroll expenses for the building’s many workers and fund the day-to-day business expenses of the offices.

On Sept. 4, Jones relates, two unidentified intruders entered the building during business hours and stealthily made their way to a half-floor on the upper level of the building where they hid until the doors were locked and night fell. When all was dark and quiet, the would-be robbers slunk to the vault in the office. They spent the next several hours swilling from a bottle of whiskey as they dug their way through 14 inches of concrete and iron on the vault’s east wall.

At the time of this attempted robbery, Jones says that there was $1,250,000 in gold known to be in the vault. She shares that this gold would likely have been in sacks or possibly bricks, visible to the thieves as they chiseled through the thick barrier wall. The mere sight of it would have fueled the criminals’ greed and their desire to succeed in their nefarious mission.

But it was doomed to be the heist that wasn’t. Though the men were able to infiltrate the vault’s wall far enough to see and even touch the gold inside, they were ultimately deterred by the vault’s iron crossbars and ran out of time as the sun rose over the nearby hills.

As dawn broke, the robbers threw a rope out a second-story window and escaped empty-handed. They were never apprehended or identified. According to Jones, the burglars left behind a lantern, a crowbar, three chisels, a handkerchief and their bottle of whiskey with only a swig left in the bottom. Perhaps the alcohol was the reason that the men failed to notice that the door to the impenetrable room had in fact been unlocked all along!

FLATIRON BUILDING, 1507 MAIN ST.

How does a new owner of an old building manage to unlock a vault with an unknown combination? With a whole lot of luck, it turns out.

Kevin Duffin and his wife Patricia purchased the Flatiron Building in 2014. This historic structure, once home to Riverside Iron and later the Wheeling Steel and Iron Company, boasts a vault on every floor. Why so many?

“Probably because the company had several divisions,” Duffin surmises. “The roofing division was on one floor, the coating division on another and so on.” Each division would have kept separate books and stashes of cash for payroll and expenses.

In 1964, the building was purchased by Nick and Grace Karnell who had offices for their real estate business and other ventures in the building for many years. The Karnells eventually sold the building and it changed hands a number of times prior to 2014.

When Duffin purchased the building that year, the vault in what had formerly been Nick Karnell’s main office was still locked shut. Dreaming of possible riches inside, Duffin set about trying to find someone with the ability to crack the safe’s combination lock. The closest such person was in Florida, but he agreed to visit the building and give it a shot.

One day shortly after arranging for this locksmith to travel to Wheeling, Duffin shares that he was on a ladder on the building’s south side cutting away old cable wiring when a man on a bike came from the direction of the Heritage Trail and rolled to a stop near the bottom of the ladder where he was working.

“What are you doing there?” the bicyclist asked Duffin. He explained that he was cleaning up the building and preparing it for renovations. The two struck up a conversation. It turns out that the random bike rider was none other than the son of Nick Karnell. When he mentioned that his dad’s office had been in the building years ago, Duffin offered to show it to him. Then he had a thought … would the younger Karnell possibly recall the combination to the ancient vault in his dad’s former office? His answer was, “Maybe.”

His first attempt at it failed, but he had another idea. Karnell asked Duffin to unscrew the switchplate on the light switch box outside the vault door, explaining that his parents sometimes hid important information in odd places. Sure enough, when Duffin removed the switchplate, the pair uncovered a scrap of paper with the combination written on it. Within minutes, they had gained entrance to the vault.

Duffin was saddened to find the vault totally empty of treasure, but relieved that he didn’t have to pay a locksmith from Florida to come and pick the lock on the strong room. He notes that the locks on all of the building’s vaults have now been disabled as a safety precaution.

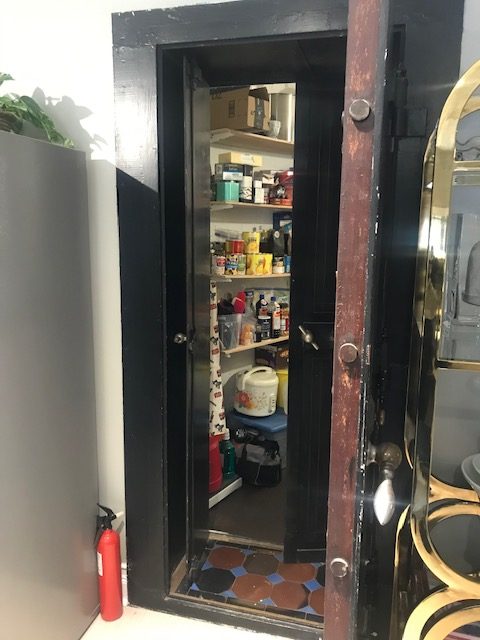

Today, that vault is a pantry and storage area off of the kitchen in one of the seven Flatiron apartments. There are similar vaults in two other apartments as well as a large one in the coffee shop on the first floor. Duffin notes that the locks on all of the building’s doors have been disabled as a safety precaution. He said that the vault in one of the apartments has particularly attractive tile flooring and would have actually made a lovely kitchen, but the incredibly thick concrete and iron walls made it nearly impossible to run modern wiring into it. Each vault has a double set of doors that would have locked separately. Duffin explained that the inner doors would have been kept closed during business hours and both sets of doors would have been closed and locked at the close of business each evening.

OHIO VALLEY PRIDE CENTER, 1320 MARKET ST.

(FORMERLY THE KING’S JEWELRY BUILDING)

The building at 1320 Market St. has been home to a number of businesses over the years, but most of us probably remember it best as the one-time flagship store of King’s Jewelry.

Online research indicates that the building itself was built in the early 1900s as an annex to the Hub department store. The Hub was a popular clothing store founded by Moses Sonneborn in 1891. The original building was located next door to the Pride Center at 1324-1330 Market St., an address which today is an empty lot.

Jack Carbasho, president of Ohio Valley Pride, the building’s current tenant, tells Weelunk that the vault remains much as it was when King’s used it to protect their inventory of diamonds and other jewels. A drawer on one wall still bears a label that reads “WATCHES.” There are many shelves where trays of rings, necklaces and other baubles would have been stashed out of sight for safe keeping at day’s end. It appears that King’s owners were prepared for the possibility of becoming locked in the vault, as it is equipped with back-up lighting that activates when the electricity goes out and an old telephone complete with a list of emergency phone numbers that appear to pre-date the existence of Wheeling’s 911 system.

FORMER POSIN’S JEWELRY STORE, 1306 MARKET ST.

1306 Market St. has a long history of housing jewelry dealers and retail stores. In 1901, Jacob Grubb opened a storefront in the building. Grubb was the first dealer of diamonds, watches and other jewelry at this address.

Grubb, a renowned high-wheel bicycle athlete and one-time mayor of the city, was also a highly-skilled optician in the area — a true jack-of-all-trades. He remained in business at this same location until his death in 1917. Distraught by financial and health concerns, Grubb committed suicide in the back of his building near where the vault would later be installed. He ended his life by ingesting potassium cyanide, a chemical used to clean jewelry.

Several other jewelers would call this address home over the years. The building also housed purveyors of hats, clothing and shoes. The upper floors were utilized by tailors, insurance agents and other business ventures of the time.

In the 1930s, the Posin family opened their long-time jewelry business on the building’s lower level. The family purchased a secondhand Mosler vault from a bank in Hamilton, Ohio, outside of Cincinnati and moved it to their Wheeling store. The vault was installed in the back of the retail space on the first floor. Though the nearly-century-old vault’s door is a bit out of alignment these days, the inside still bears witness to the days when Posin’s kept watches and jewels inside it. The shelves within are still labeled for Bulova watches and repair orders.

The Mosler safe company was famous for manufacturing vaults and safes of unusual strength, including a bank safe that withstood the nuclear blast of Hiroshima. The Posin’s vault boasts a ventilation system made by Mosler. Ventilation and communication systems were often added to commercial strong rooms as a precaution in case a person found himself locked inside. Thieves were known to lock employees in vaults during robberies, as they believed that freeing them would be the most urgent priority of responding law enforcement, thus slowing their pursuit of the thugs.

Former owner Samuel Posin says that the vault also had a telephone inside. “It was for emergencies, and it was also used occasionally if someone suspicious entered the store, and we needed to call the police or others without being seen,” he explains. Posin also recalls that traveling jewelry salesmen would sometimes stash their cases of gems in the vault so that they could enjoy dinner at a local restaurant free from concern about the safety of their wares.

IMPERIAL TEACHERS’ STORE, 2347 MAIN ST.

(FORMERLY THE CENTRE WHEELING TANNERY COMPLEX)

Teachers today know this location as a favorite spot for purchasing classroom supplies. But that’s not what John G. Hoffmann had in mind when he erected the brick buildings at the corner of 23rd and Main streets.

Hoffmann was the owner of Centre Wheeling Tannery, which was founded in 1849. This tannery was one of the nation’s earliest and most well-known industrial tanneries. In those days, horses were the major means of transportation, and saddle leather was a valuable commodity. Tanneries transformed perishable skins into durable leather for saddles, horse tack, shoes and many other consumer goods of the era.

Philip Jackson, the current owner of the building, shares that the Hoffmann family started the business on Wheeling Island. However, following a fire there, the Hoffmanns moved the business to its Main Street location in 1857. The tannery’s premises “included everything from the alley to 24th Street to Main Street to the river,” Jackson says. “The tanning vats were on the part now occupied by Contractors’ Supply. I think the hides were stored on the lot between the Teachers’ Store and Christmas Store and there was a wooden structure where the Christmas Store is.”

The main vault inside the building on the second floor is situated inside a room whose door is marked “General Office.” The vault itself still bears the name of its original owner, J.G. Hoffmann & Sons Co., meticulously hand-lettered across the top. The former tannery also has a second slightly smaller vault in another room on the second floor.

Eagle-eyed readers may note that several of the vaults pictured in this article were made by different vault companies all located in Cincinnati, Ohio. Various internet sources indicate that Mosler-Bahmann & Company was in existence initially but the two families later had a falling out, and the Mosler family struck out on their own, becoming Mosler Safe Company.

Victor Safe & Lock Company also manufactured vaults and safes during that same period. In those days, safes and vaults were one of the top commodities made in Cincinnati, likely because of several factors. First of all, Cincinnati was a federal reserve center with a large number of financial institutions that would be prime customers. Also, the area was home to several major manufacturers of iron and steel, which would be vital components in the making of vaults. Finally, Cincinnati was centrally located within several hours of most of the nation’s population at that time, with nearby access to both river and rail transportation for ease of transportation of the hefty strong boxes.

SHADOW KNOLL, 110 CARMEL ROAD

Today Shadow Knoll is a multi-unit apartment complex, but in the early 1900s, it was the home of Henry G. Stifel, grandson of Stifel Calico Works founder J. L. Stifel. Henry was a vice president of the famous calico works and had the spacious hilltop mansion built for his family.

One wing of the basement was the men’s billiards room, where the men gathered before the grand stone fireplace in “Downton Abbey” fashion to enjoy their libations and a game very similar to modern-day pool. The family vault was also located within the male domain of the billiards room to protect the Stifel family valuables.

Nowadays, the billiards room is a large apartment, and the former vault, door still intact, serves as the unit’s attractive and efficient kitchenette.

In the Wheeling of days gone by, treasures were protected within the walls of these interesting vaults. Today, the vaults themselves are the treasures; pieces of local history with tales yet to be revealed behind each ponderous door.

• A lifelong Wheeling resident, Ellen Brafford McCroskey is a proud graduate of Wheeling Park High School and the former Wheeling Jesuit College. By day, she works for an international law firm; by night, (and often on her lunch breaks and weekends) she enjoys moonlighting as a part-time writer. Please note that the views expressed in her writing are solely her own and do not necessarily reflect those of anyone else, including her full-time employer. Through her writing, Ellen aims to enlighten others on causes close to her heart, particularly addiction, recovery and equal rights. She and her husband Doug reside in Warwood with their clowder of rescued cats, each of whom is a direct consequence of his job as the Ohio County Dog Warden. Their family includes four adult children, their spouses and several grandkids.