As flowers are blooming, seasonal allergies are flourishing, and warmer weather is in the air…so is spring cleaning. Today, members of Volunteer Wheeling can be seen cleaning the streets and organizing the community. This type of volunteerism is part of a long tradition in Wheeling; in the early 1940s, African American community members organized city beautification projects in Wheeling as part of a larger national “Clean Block” Campaign.

“A Real War on Dirt”

The Clean Block campaign started in 1934 in Baltimore as an annual community beautification project in African American neighborhoods.1 The campaign was originally the brainchild of the Baltimore Afro American—one of the most prominent Black newspapers in the US. The campaign eventually spread out to select other cities—including Wheeling. It became a national “real war on dirt.”2

Mostly involving children and teenagers, the campaign was structured as a contest; each block competed against each other. They were judged by local leaders and the most presentable block would be awarded some type of prize.

Wheeling’s campaign lasted for three years—1941 to 1943—and involved the participation and cooperation of several hundred local children and teenagers.

Wheeling’s Clean Blockers

At 8 am, the Lincoln School bell—Wheeling’s segregated Black public school—would ring to announce the first day of the contest.3 The contest would run for a few weeks sometime between May and July every year, held during the summer months so school children could participate.

The campaign was organized by adult advisors, but most of the actual activities were conducted by neighborhood children and teenagers, ages approximately 8 to 15. The first head director was Margaret Berry—mother of the famous saxophone musician, Chu Berry.4

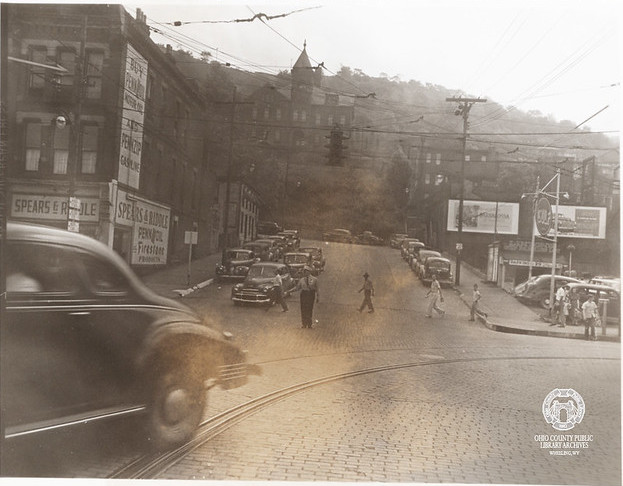

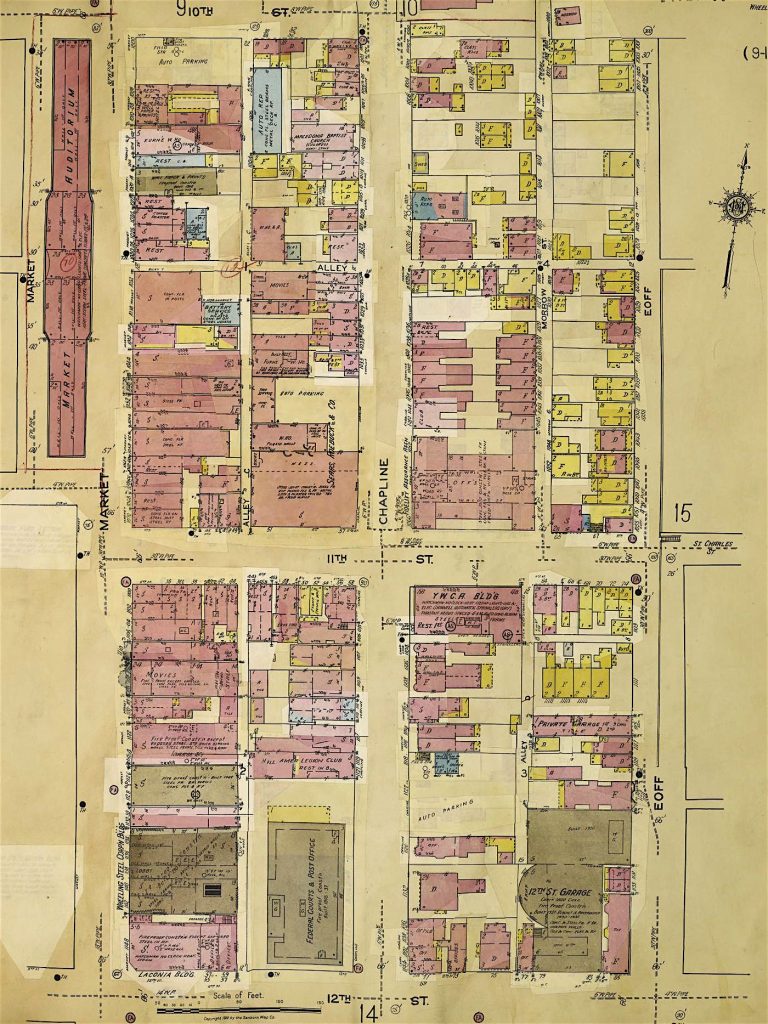

In 1942, according to the Wheeling Intelligencer, between 100 and 200 Wheeling children participated in cleaning their local streets, yards, and neighborhoods. Participants would form teams and select a block to dedicate their time and energy to beautifying. Most of the blocks were located in what was the heart of Wheeling’s African American community—Morrow St., Alleys 7 and 8, and 11th St. Groups also tackled other areas in Wheeling, like various locations on Chapline, Eoff, Main, Market, 23rd, and 26th Streets.5 The Intelligencer would run little updates throughout the contest and often list out the members of each team, complete with captains.

Supposedly, the children would sing as they worked with a different song chosen each day— Volunteers sang “Mary Had a Little Lamb” during their first cleanup day in 1941”6 They even wrote their own team songs, with creative titles like “Eoff Street Clean Blockers” and “Thirteenth Street Clean Blockers.”7

The tasks ranged from cleaning up streets, planting flowers, sweeping steps, and even painting houses. Supplies, like flowers, were often donated by community members and distributed amongst the teams.8 Just during the 1941 campaign, Wheeling reported to the Baltimore Afro-American that “200 yards cleaned, seventy-five window boxes erected, houses painted, YWCA [Blue Triangle] painted, fifty houses had doorways and windowsills painted, 100 back yards cleaned, and thirty-five front yards beautified.”9 It must have been quite the sight!

Even when the competition wasn’t active, “Clean Blockers” were still hosting other community events. Fundraisers such as a cutest baby competition and street carnival raised money for supplies and other campaign support.10 After the conclusion of the first year of the campaign in 1941, the Clean Block campaign teamed up with the Ohio Valley Board of Trade to organize a free picnic at Wheeling Park for all the child participants.11

In Wheeling, the successful end of the campaign was celebrated by the awarding of prizes to the best block. First place received an American flag and everyone enjoyed an evening of entertainment by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Black orchestra—a New Deal program.

All Good Things Must Come to an End

Although popular while they lasted, the Clean Block campaigns in most cities eventually lost steam and no longer exist. Baltimore, however, where the project originated, has continued the Clean Block campaign into the 21st century.12

While it is obvious that there was a fair amount of participation and support for the Clean Block campaign in Wheeling, it is unclear why it only lasted three years. While the Clean Block campaign was a program that got national attention, there have been other city beautification efforts—ranging from formally organized projects to spontaneous individual undertakings. Maybe the Clean Blockers of the 1940s can inspire today’s city residents to get involved and clean up Wheeling…

Help Beautify Wheeling Today!

If the “Clean Blockers” of the 1940s inspired you to help make Wheeling a cleaner and more beautiful city, lend a hand with Volunteer Wheeling! Volunteer Wheeling is a group of local community members that comes together about once a week to tackle small beautification projects in Downtown Wheeling and the surrounding neighborhoods. As the group expands, they are looking to mix up their activities with some larger long-term beautification projects…but don’t worry! The smaller-scale clean-ups aren’t going anywhere! It is super easy to get involved—you can volunteer as much or as little as you would like—most projects typically last 1 to 2 hours.

Volunteer Wheeling’s leader, Ellen Gano understands that “it would be better if people just didn’t litter in the first place,” however, she is “so energized that a growing number of people are getting on board with Volunteer Wheeling and helping to make the city cleaner. The transformation this group makes to an area in just an hour’s time is pretty incredible!” Volunteer Wheeling started out as a small group of residents wanting to make a difference and has organically multiplied as more people have learned about the projects and decided to pitch in. Even though Volunteer Wheeling’s projects aren’t energized competitions like the Clean Block campaign of the 1940s, all participants—young and old—are always needed for city beautification.

To read more about the organization’s projects, check out articles here and here. If you want to learn more about Volunteer Wheeling’s future projects, join the community Zoom meeting on April 21 at 7 pm. To join the meeting, sign up for the Volunteer Wheeling newsletter on their new website!

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.