He was a kid whose father was very involved with the local horseracing industry and whose mother didn’t much approve of what took place at Wheeling Downs.

He knew “Big Bill” Lias, and although he had heard he was a mobster, he still believes today that he was one of the nicest men he’s ever met.

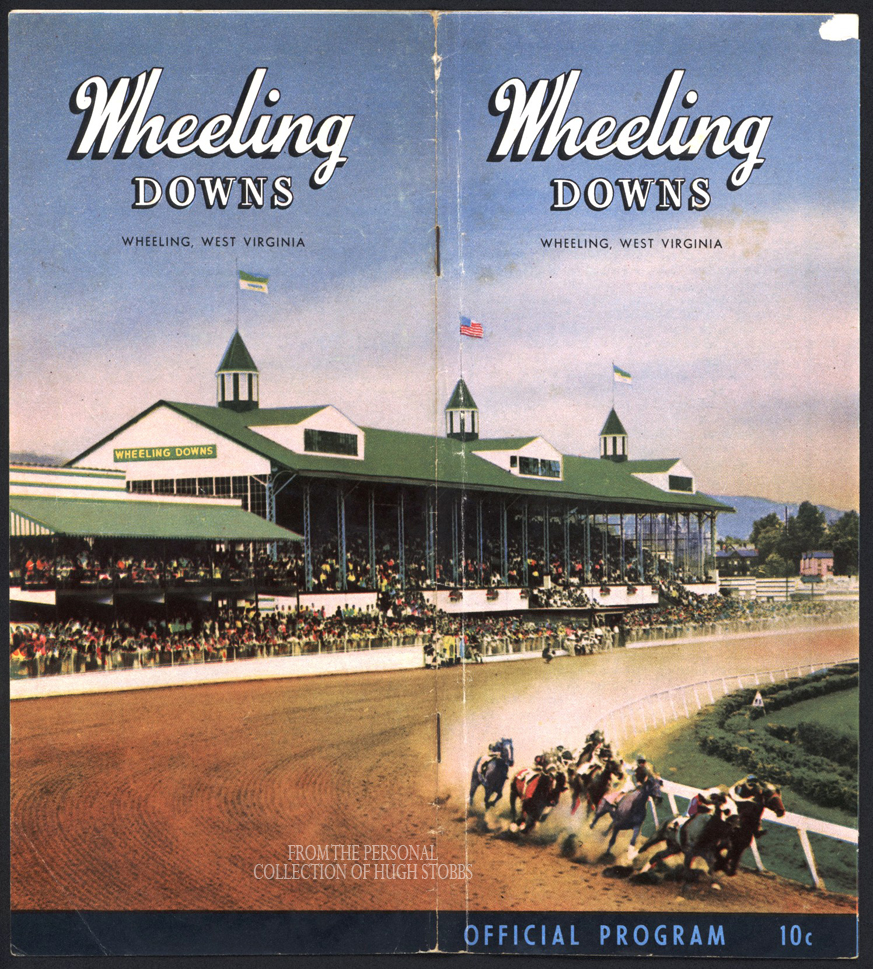

And Hugh Stobbs received betting tips, and he used them to win fast cash at the Downs, a horseracing track on Wheeling Island before the switch was made to live greyhound racing in 1976. Not only was he a young patron of the track when accompanying his father, but Stobbs also was employed there beginning in high school and until he was 25 years old.

“When I was a young kid, my dad would go over with some of this friends, and he’d take me along, and I would meet all of his friends,” he recalled. “My mother didn’t like that much, but that’s how I became familiar with the racetrack.

“When I started working there, I was the person who would take 50 cents for people to park in the lots, and there was also a charge to get into the track,” Stobbs said. “I worked there for 12 years, and when I left, I was the admissions director, and that was a pretty nice job, I have to admit, because ‘Big Bill’ made sure that the people he trusted were compensated pretty well.”

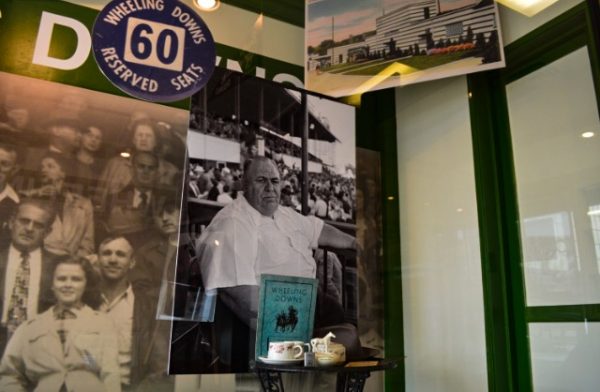

His reference to “Big Bill” is directed at Bill Lias, the leader of organized crime in the Wheeling area for several years. His legitimate business for many years was owning Wheeling Downs, and items pertaining to Lias were included in the items Stobbs has loaned to the Ohio County Public Library for a pair of displays

“The people from the library reached out to me through Margaret Brennan because Margaret has known for a long time that I am collector of some things,” he explained. “She had seen all of the things that I’ve collected through the years that concerned Wheeling Downs, and she mentioned it to the people at the library.

“So now there are a couple of displays,” Stobbs said. “Erin Rothenbueler and Sean Duffy from the library came over to my house and picked it up, and now one display is in the front windows of a building on Market Street in downtown Wheeling, and the other things are on display at the Ohio County Public Library. Plus, they had (Sandra Caldwell) McClelland Signs enlarge a lot of the photos, and she made the displays, too. It really looks great.”

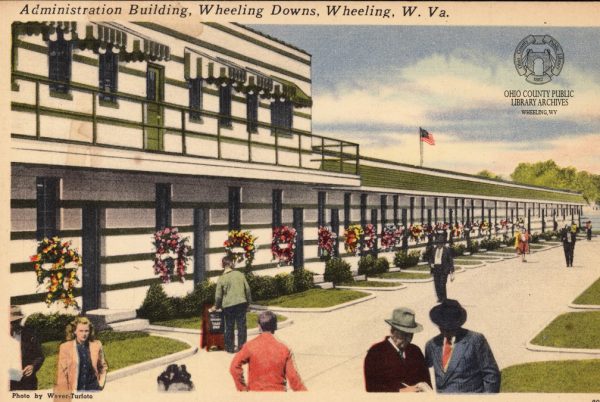

What Stobbs cannot offer those who visit with the collectibles at the library or along Market Street in downtown Wheeling is the beauty he appreciated each time he reported to work. One postcard enlarged by Caldwell displays the track’s apron, a trackside area surrounded by manicured lawns, crack-less sidewalks, and flowers below every window.

“It was really, really a beautiful place because that was how ‘Big Bill’ wanted it to be,” Stobbs remembered. “They had a paint crew there, and those guys would paint the whole place, and when they finished they were told to start over. That’s how Bill Lias did business. It had to be beautiful all of the time.

“The whole place was painted white and green, and there were flowers everywhere,” he continued. “Back in those does there was a big lake in the infield of the racetrack, and during the summers he would have flamingos brought it to live in that lake. If he didn’t have the flamingos, he would have a paddle boat that would go back and forth in that lake.”

“They held eight races a day, and they could have only eight horses in each race because the track was only a half-mile track. At one time, Wheeling Downs was said to have the best half-mile track in the country,” Stobbs reported. “People came to Wheeling from all around because Wheeling Downs was known as a really classy place, and people wanted to be there.”

“One of the Nicest Guys”

Everyone knew “Big Bill,” for good reasons and for bad ones, because he ran rackets that were not legal, like the wagering that took place at his racetrack. Illegal gambling, stolen goods, bootlegging, and prostitution were his bailiwicks during his heyday as the leader of Wheeling’s organized criminal activity.

The reach of his rackets extended well past Ohio County’s border, and one reason why was the fact that Wheeling Downs attracted those in the gaming business as close as Ohio and as far as New York and New Jersey, Stobbs said.

“Gambling back then wasn’t like it is these days,” he said. “If you wanted to bet, you had to go to places like Wheeling Downs, but that was then when there weren’t too many racetracks like that. Plus, gambling wasn’t legal the way it is now, so if you wanted the horses, you had to come to Wheeling, and it seemed like they came from everywhere.”

But the track wasn’t the only reason tourists visited Wheeling during the days Lias owned the racetrack; the city was a mecca of activity thanks to a downtown district littered by bars and pool halls that fronted gambling in back rooms. It was normal and therefore accepted by the residents because the crime rate was low, and anyone who participated, did so on their own volition because Lias and his boys didn’t recruit.

“My uncle, Carl Bachmann, was his attorney in Wheeling, and ‘Big Bill’ was one of the nicest guys I think I’ve ever met,” Stobbs insisted. “When I worked there and it was Christmas time, he would ask all of us for names of people who were in dire need of something for Christmas. When we went out to deliver what he had bought for those families, it would take two of us to carry it all in to the house.

“There would be a whole ham, a turkey, the works, and he did that every year I worked there,” he continued. “I know some people hear those stories these days and don’t really know if it’s true, but I can tell you it was definitely true because I was in the middle of it.”

Stobbs, who performed a presentation at the library close to two years ago, had heard the rumors about Lias even before the IRS seized Wheeling Downs as an action under the tax evasion case against him, but when this former employee remembers him, it as a genius and not as a criminal.

“None of that has changed my mind about Bill Lias,” Stobbs said. “He was a good person to work for because he really did take care of his employees. I know the federal government had taken the track away from him because of his tax issues, but it didn’t take long for them to give it back to him, now did it?

“The federal government lost all kinds of money when they had taken over the operation of the racetrack, so they brought him back to run things again, and that made him the second highest paid federal employee in the country,” he continued. “He didn’t own it then, but he was in charge of the management, and everything turned profitable again because it was a class act. That man really did know what he was doing.”

Tax evasion was the crime Lias was accused of in 1952 and was later convicted for, but the accusations against him reached out to the operations of sports books, brothels, truck hijackings, and even murder and attempted murder.

None of it ever mattered to Stobbs,

“I’ve heard that story about his first wife, but no one ever proved it,” he said. “And I know he was questioned about the Hankish bombing back in 1964, but no one ever proved that either.”

Canucks, Hubert, and Fun

When he thinks back about his dozen or so years as an employee at Wheeling Downs, Stobbs can’t help but smile because the images of a city once known as “the Reno of East” come clearly back to his memory.

Stobbs made an impact in Wheeling in several ways, one of which involved the Elby’s Distance Race, a 12.4-mile road race that evolved into a world class event that attracted international competition to the streets of the Friendly City. These days, Stobbs is the race director for the annual Veterans Day Race, an event staged in honor of his wife, Lois, each November, to raise funds for disabled American veterans.

“Wheeling Downs, at one time, had night racing, too, and this one evening we had these men from Canada come to the racetrack and one of them asked me about the stadium,” Stobbs said. “One of them told me that they had never seen American football before and wondered if they would have the chance while they were here. I told them that the Wheeling Ironmen played a lot of games there and they asked if I could get them in.

“I knew the gate man over there so that Sunday the Ironmen had a game, and I got them in so they could watch American football. Then, two weeks later, they pulled up to the track in their Cadillac again, and one of them said that they owed me a favor,” he recalled. “They had brought some horses down from Canada, and they told me that those seven horses were going to win seven races that night. I had $250 in my pocket, so I put money down on those seven races and won every one.”

One after another, the Canadian thoroughbreds claimed victory.

“I had told my relatives that worked there, and I told my dad, too, and we all won those seven races, and I had I had $5,000 in winnings with me when I was walking out,” Stobbs admitted. “I really thought it was my night, so I went down to Billy’s Bar in South Wheeling to get in on a Barbooth game, and that game moves very quickly.

“But by the time I was done, I was back down to my original $250,” he said, “so I guess it wasn’t really my night.”

Stobbs also tells a couple of stories about Thunder Lee and Wall Miss.

“My dad had two race horses that he was given by one of the owners because that owner couldn’t pay his feed bill,” he explained. “My dad paid that bill and he got the horse even though my mother wasn’t too happy about having those horses. He put her name down as the owner of those horses so it was really neat for me to find a program on eBay that had Wall Miss listed in it, and there was her name, Mrs. H.N. Stobbs.

“That program was in pristine condition and it was from 1940,” he said. “I couldn’t believe that after 75 years or so I was able to find that with her name it. That was really special for me.”

And then there was Hubert, one of a number of jockeys that loitered at the racetrack while lobbying horse owners for a chance to ride to earn a living off the industry.

“Back in those days there weren’t very many black jockeys here in Wheeling and when my father had his two horses a black man named Hubert McKinney approached him and asked if he could be my dad’s jockey,” Stobbs remembered. “He told my dad that he had a wife and two kids and that not too many owners were giving him a chance. He said he was getting maybe one ride per week.

“I remember my dad saying to him, ‘Hubert, you can ride them, and if you ride them good, you can keep on riding them, and Hubert did pretty well with Thunder Lee and Wall Miss,” he explained. “If the other owners were critical of my dad for doing that, he never said anything. My dad didn’t really care about those things. People were people to him.”

Stobbs remained employed at Wheeling Downs through the 1950s, a decade during which the federal government was paying much attention to Lias, his income, and his status as an American citizen. In 1960, however, he made the difficult decision to resign as admissions director to spend more time with his wife and children. Following his commencement from West Virginia University, Stobbs gained employment with Wheeling Steel, and Dottie and he were parenting two children.

“But Wheeling was fun back in those days,” he admitted. “It was fun, and part of the reason was that ‘Big Bill’ wasn’t letting anyone get robbed in Wheeling. It started at Zeller’s Steak House and just seemed to spread all through town. Back in those days there were bars everywhere, and there were so many people along Market Street that some people would have to walk in the street because there wasn’t any room left on the sidewalk.

“Back then you really didn’t hear about any crime and you didn’t think about the organized crime because that was just normal to everyone,” Stobbs remembered. “I’ve heard a lot stories about those things since but it really wasn’t that big of a deal because it was all surrounded by class and Wheeling Downs was the epitome of class.”

(Photos by Sean Duffy, Ohio County Public Library)