Photos Courtesy of Joe Roxby and Don Feenerty Photography

Weelunk urges you to attend Fort Henry Days this weekend!

For local frontier history lovers the 1782 siege of Fort Henry holds a unique place in their hearts. Thanks to best-selling authors like Zane Grey and Alan Eckart it is easily the best- known event in local history. To the citizens of the upper Ohio Valley it is something of the local combined version of the Iliad and the Alamo. In defense of that idea, the personalities of Fort Henry’s defenders were every bit as fascinating as any of those who stood at the walls or Troy or manned the mission at San Antonio. The most notable difference between our local siege and those two more famous ones is the defenders of Fort Henry were successful. They did not die in a blaze of glory but lived on another day. The fictional literature that has been written about them has given them their due glory, but it has often tended to obscure the truth. The object of this article is to give the modern reader an accurate reconstruction of the battle with the best available eyewitness accounts.

At the beginning of the September of 1782 there was very little war news to cheer the citizens of the upper Ohio Valley. The guns along the Atlantic and in the east were quiet but this was clearly not the case in the west. Indian raiding that year was probably the deadliest since 1777, known as the year of the bloody sevens. There were more ominous notes for Fort Henry in 1782. In late May and early June Col. William Crawford was killed leading an expedition against the Indians at the Upper Sandusky. It was the same Crawford that had brought 400 men from Pennsylvania to build Fort Henry in the summer of 1774. Most probably it was his transit and chains that laid out the walls and bastions of the fort and he was the first commander as well. He would die one of the most horrible deaths recorded during the Indian Wars. Late in July of 1782 an Indian war party finally settled accounts with the hero of the first siege of Fort Henry, Sam McColloch. While out scouting with his brother John, he rode into an ambush about five miles from his home and this time there would be no escape for the gallant Major. It seemed that many famous figures whose history was connected with the fort were coming to evil ends.

From the information gleaned from the enemy camp, it was certain that an attack was imminent. John Slover left no doubt of that. Slover was a guide for the Crawford expedition. He had the misfortune of being separated from the main army during the retreat and was captured a couple of days later. Before his fate was to be decided by the Indian war council he was allowed to sit in and hear the speeches of the war chiefs. During his youth he had spent several years in Indian captivity. He spoke Shawnee like a Shawnee and was well versed in other Indian languages as well. One of the conclusions of the group was that the fort at Wheeling must be destroyed. The other was that Slover was to be burned. Slover was bound to the burning stake and a fire was started. He prayed and then felt calm about his pending demise. In an act of incredible Divine Providence a rain cloud appeared out of nowhere and extinguished the blaze. Early the next morning a few hours before his next date with death, Slover managed a daring escape. Near the middle of June he made his way to Fort Henry with the news that an attack would be coming.

In spite of all the warning and attacks that summer the people around the fort became careless about their security. Years later Lydia Boggs Shepherd would recall:

The people of the fort became careless, and even neglected to close the fort gates at night. Jonathan Zane said he would not stand sentry: he was not afraid. And others said they would not watch for Jonathan Zane’s family if he wouldn’t do it himself: they were as brave as he. (1) That sort of reckless disregard for the enemy sounded like a recipe for disaster, and it nearly was.

The Indians clearly believed the old military maxim that time spent reconnoitering the enemy is not wasted. At least three days before the attack Indian scouts were as close to the log walls as cover would permit, observing all that went on in the fort. From the aborted siege in 1781 they knew that the cannon on the firing platform in the center of the fort was a fake and the palisades were in bad repair. The fort was built in 1774. By 1782 several of the logs that made up the walls were rotten enough to fall over with a good shove. In checking the defenses, the enemy scouts got close to the fort, perhaps too close. A couple of nights before the battle a group of women abandon the walls in the darkness to seek relief. An elderly woman referred to as “Old Mrs. Connard” actually urinated on one of them. She could certainly claim being close quarters with the enemy and left no doubt of her low opinion of them.

The defenders had scouts out as well. Intelligence came back piecemeal and was contradictory. Stephen Burkham and another scout discovered a trail to the east of the fort. They also believed they heard Indians picking their flints. Andrew Zane and another group had gone to retrieve a keg of whisky they had hidden along the road. He said that he had observed the same trails and believed them to be made by cattle.

One preparation that the frontiersmen made some time that summer was to raise a company to garrison the fort. A later pension application would note that their company’s captain was Silas Zane, and it was not affiliated with any regiment.

Earlier that May and prior to Crawford’s defeat, fifteen volunteers could not be found to man the fort. For a company to come together now indicated that the settlers were at least aware of their peril. Another very important preparation was the addition of a small cannon. Several men had been sent from Fort Pitt to guard Fort Henry in the fall of 1781. Lt. Mathew Neely brought a small, personally owned cannon with him, which he left at Fort Henry when he returned to Fort Pitt. The style was referred to as a swivel gun. Those personally examined by the author were roughly the length and thickness of a man’s arm. The weight ran about 70 pounds and the bore about two inches. It was attached to a Y-type mounting and easily fixed to a ship’s rail or a tree stump. It would play a most important role in the fight to come. The piece could be loaded with undersized missiles and used as a giant shotgun or with solid shot against an enemy under cover.

The attack commenced in the late afternoon of September 11th. It started around 3:00 pm as scout John Lynn appeared breathless at the gates of the fort. He informed those present that a huge Indian war party was on the way and no more than two hours behind him. The swivel was immediately fired. It alerted all within hearing of the impending attack. The fort quickly became alive with activity as families began streaming in.

“Instant preparations were made for defense…The men, women and children all went to the river with buckets, not liking to venture to the spring next to the hill by the woods. Balls were run, camp hatchets stuck in the pickets, along the portholes, with orders for the women, if the Indians undertook to scale the pickets, to chop their fingers off… The Indians soon surrounded the fort.” (1)

From the description of the scout, everyone realized that a major assault was underway and this was no mere raiding party. Captain William Boggs, the father of Lydia Boggs, mounted a horse and immediately left for Catfish Camp (Washington, PA) to get reinforcements. He rode north along the Ohio for a mile and ran into Abraham McColloch riding toward the fort. The two heard the swivel gun fire again and immediately put the spurs to their horses.

If those inside the fort were busy, those outside were wasting no time either. Sixty or so Indians combed Wheeling Island for any resident who might be caught unaware, but they found no one. By 6:00pm the fort was surrounded. From the hill on the east side of the fort British Rangers prepared to parade the Union Jack up to the gates and demand the surrender of the fort. In a gesture worthy of the Alamo, the.swivel gun was fired at the enemy flag as soon as it appeared. The message was clear, come and take it. Both sides now started to take their measure of each other, and try their hands at psychological warfare. Just by their presence the Indians must have had considerable effect on those in the fort. A small Indian raiding party of a dozen or so could paralyze an area. To know that at least 200 were outside the fort must have been chilling. Lydia Boggs Shepherd offered this description:

“ When the flag was seen, the swivel was fired at the flag. The emblem now disappeared. At this instant all the people in the fort raised a defiant yell—men, women and children, all ordered to do throwing up hats, caps, brooms, sticks and everything within their reach. Then even the smallest children, too small to comprehend it, joined most lustily in this bravado, some hollering “Come on, we are ready for you” and shooting occasionally. All this was done to convey the idea that the fort was well defended by brave and fearless men. Nor were the enemy silent. They mingled their yells and whoops with those within the fort, and shooting down hogs, cattle, etc. And for a time all was noise and confusion. (1)

Adding a touch of comic relief to a deadly serious scene she also added: “Just before the cannon was fired on the flag, an old red cow was passing by in the road. The flagbearer gave her a blow with the flagstaff, and she ran down to the fort, and was let in. “ (1)

At the west wall another bizarre scene took place. Several Indians had gotten possession of women’s undergarments they found in the cabins. From a safe distance on the island several of them dressed and danced around in their new plunder and taunted the defenders.

The firing of the little cannon served the British Rangers with three unpleasant realities. There would be no talk of surrender, no chance of an ambush, and the defenders had an artillery piece. By 1782 the frontiersmen had been fighting Indians long enough to discover a few things about their adversaries. The first was that Indians did not care for siege warfare, as they fought as light infantry. They were the true masters of concealed ambush, feigned retreat and the “run and gun” style of warfare in the forest, but they would seldom press an attack for longer than a day on a vigilant enemy in a good defensive position. The Sullivan campaign of 1779 also clearly showed they had an aversion to artillery fire.

About that time a boat with three men appeared at the shore below the fort. As it touched the shore the men ran for the closest entrance with bullets zinging around them. All three made it safely behind the pickets and added three more defenders. Daniel (Cobe) Sullivan was the only casualty with a slight wound in the foot. The boat was carrying a load of cannonballs for George Rogers Clark.

By the middle of September the sun begins to set early. As darkness fell the psychological chess match between the invaders and defenders continued, with the invaders offering the opening gambit.

“For about two hours a most serio-ludricrous scene took place. Captain [Brandt] now called out, announcing who he was, called on the garrison to surrender, promising as good quarters and treatment as King George could afford, and that he was disposed to be kind if they would capitulate: and he added they had three hundred Indians and fifty Queens Rangers from Detroit, and the next day they would have fifteen hundred more, with cannon to batter down the picketing …They knew that the fort was chiefly defended by women and children. But if the garrison should obstinately refuse to surrender, they might rely upon it that, when taken by storm, as they would be, no quarters would be granted…”Your blood” he said “ be on your own hands.” (1)

It should have been a low point for the defenders. They were surrounded by a cruel enemy, offering no real chance of quarter. In fighting men they were outnumbered by a minimum of ten to one, and quite possibly many more times that by the next day. The number of fighting men in the fort has always been a subject of controversy. In later years Betty Zane stated there were 16. Lydia Boggs Shepherd names 25. Together with their families they may have numbered between 80 and 100. Of course there was no real choice. Everyone in the fort knew that once they surrendered, the British Rangers would be powerless to stop the bloodletting that would take place. Two years earlier, when Ruddle’s Station in Kentucky had surrendered, the orgy of Indian bloodlust was so wild it sickened the British officers present. Before anyone inside could give any serious thought to surrender Jonathan Zane delivered a fire-eating reply.

“We have no favors to ask of such cutthroat savages, villians and Tories and fiendish devils as you—Rely on it. We would never sink basely to surrendering to such a contemptable foe. We will never be taken alive—and if taken at all, it will be fighting in the last ditch. In King George’s name, you have graciously promised us good quarters: as for King George we most heartly detest his very name, and couple it with blackest infamy, and the quarters you so generously promise us are as such as you gave Colonel Crawford and his men…We have no confidence in British promises, and shall certainly not heed them, nor do we fear your threats. We have sent for assistance, and will give you hot work enough for you shortly. Come on you heathen wretches, we will soon have your scalps dangling over the gates of our fort.” (1)

As the sun set, a new moon bathed the battlefield in an eerie light. The defenders left no doubt that the fort would have to be taken by force. Making that task more difficult, Fort Henry was well situated. To the south and west, steep hillsides made any sort of rush against the wall impractical. It was also flanked by two blockhouses. Sixty yards to the southeast Ebenezer Zane had his cabin with a stout blockhouse built on to it. After his home was burned in the battle of 1777 he vowed that he would fight to the end from his own little redoubt. Forty yards to the north was another outpost. Peter Reager had a combination blacksmith-gunsmith shop located in the area of the Suspension Bridge. It is documented that Wheeling had been the scene of considerable gun repair activity since the outbreak of the Revolution. Along with Reager and his apprentice, another gunsmith named Isaac Williams worked with them. The forge could well lay claim as The Friendly City’s first true industry. Reager was joined by Conrad Stoop, along with Francis and Henry Clark. When the defenders at the forge saw the size of the invading force, they lost their nerve. As soon as darkness permitted they abandoned the blockhouse for the safety of the fort.

The enemy lost no time in taking advantage of this. Several of them took up positions in the abandoned building and began to make life tough for anyone in the forts’ two northern bastions. Many years later Betty Zane’s son, Ebenezer Clark, offered his mother’s recollection. “ My mother occupied the sentry box with her brother Jonathan and a man named Salter, and loaded their guns. The position was a post of observation, and the best marksman and those having the most knowledge of the Indian modes of warfare were selected for the place. Of course it was a prominent mark for the enemy, and my mother said she would frequently have to stop and pick the splinters out of her body, which the bullets would split off and drive into her flesh. (2)

The rifle fire from the blacksmith’s shop became so intense that something had to be done. Former artillery man John Tate began to give the enemy a taste of the little fort’s big medicine as he turned the swivel upon the trouble spot. Several shots from the little cannon literally brought the roof down on the pesky snipers. At midnight the Indian and Rangers tried to rush the fort, most probably at the north wall. Once at the walls their strategy was to try to set the pickets afire. It was a danger not to be taken lightly. Fort Henry was made of eight-year-old very dry logs. It was probably a great task under normal conditions to see that the fort was not burned down accidentally. Once the walls were breached the attackers could rush in and overwhelm the defenders by sheer numbers.

The first night of the siege would see the most violent direct assaults. Two days later Ebenezer Zane wrote: About twelve o’clock at night they rushed hard on the pickets in order to storm, but were repulsed. They made two other attempts to storm, before day, but were repulsed. (2)

After the first assault was turned back, other stealthier ones came probing for weak spots.

To help cover their movements the raiders kept up a brisk fusillade from the north. Even as the enemy probed the defenses, they traded insults with the defenders. “Passes at wit and low jesting were briskly interchanged…The Indians who took no part in these sallies at wit but seemed to enjoy it heartily.” Like young soldiers throughout the ages, the talk of the invaders turned to strong drink and women. They inquired about the presence of both inside the fort. The rangers no doubt told the girls on the other side of the wooden walls that their acquaintance with them would be a bit more intimate by morning. A tart- tongued Betsy Wheat answered them insult for insult. She was described as a fearless Dutch girl who could handle a musket as well as a man. When one of the Girtys told her that he would be in the fort or hell by morning Betsy concluded the love negotiations by telling them, “then hell is your portion, for into the fort you cannot come.” (3)

In the early morning hours they found one at the west wall. A gully in the steep hillside provided cover for a few men to approach the fort. It was a dead spot in the defenses that could not be covered by rifle fire. A couple of Indians and Rangers made it to the wall. A group of quick-thinking women came up with an improvised defense. They pulled up the hearthstones in the cabins on the west wall of the fort. They tossed the rocks over the wall and drove the enemy sappers back toward the river. During the night the women relieved men at the firing ports so they could snatch a few moments rest

The first light of the next morning revealed another problem. Two rotten pickets in the north wall had fallen. The swivel gun had fired 16 times that night and the concussion from the piece had caused them to fall. Peter Neisinger quickly put them up before they were discovered by the enemy. Fortunately, a small group of peach trees hid them from the enemy’s view. .

Two days later Ebenezer Zane reported to Gen. Irvine: About eight o’clock the next morning, there came a negro from them to us, and informed us that their force consisted of a British regular captain and 40 regular soldiers and 260 Indians. The Indians kept a continual fire the whole day. (2)

Probably not wanting to sacrifice one of their own, a slave taken captive by the Indians on the Holston River was forced to try to get to the walls in daylight. When he was slightly wounded by a lady named House, he decided to attempt surrender. He was allowed into the fort, but his greeting committee consisted of Betsy Wheat holding a tomahawk. His intelligence was most timely as he gave the defenders an accurate picture of the enemy and their true numbers. He also noted that the little swivel had been particularly galling to the Indians.

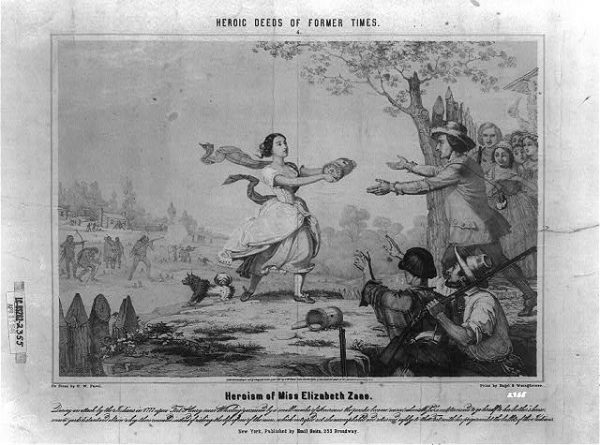

About noon came the emotional highpoint of the battle. Another crisis had developed; the fort was out of gunpowder. The swivel gun that was so valuable in keeping the invaders at bay had used up what was in the fort. Some months earlier Ebenezer Zane had asked for and was granted 40 pounds of gunpowder from General Irvine at Fort Pitt. So that it would not be pilfered he kept the bulk of it in his own cabin. Under ordinary circumstances the powder kept inside the fort would have been more than enough. As a rule Indian attacks usually lasted no more than one day, but this was anything but a small-scale raid. The presence of British rangers and the size of the invading host made it clear that the usual rules would not apply. A call was put out for a volunteer to run to Zane’s blockhouse and bring back more. Sixteen year-old Betty Zane stepped forward saying that should she fail “she would be missed less than a man.”

Years later her son recalled the story from his mother’s own recollections. “I have heard my mother tell the story of the Indian wars, the siege and her exploit of carrying the gunpowder many times. She never spoke of it boastfully or as a wonderful matter, but in early times we didn’t have newspapers or books, and on long winter evenings all we had to amuse us were stories of the early settlers, Indian fights and escapes.… When consent was gained she stripped herself to her shift and petticoat so she could run fast. As soon as she appeared the Indians seemed taken by surprise and exclaimed ‘A Squaw, A Squaw’ but never offered to disturb her. When she reached Col. Zane’s they tied a table cloth around her waist, poured a keg of powder in and she started with it on a run to the fort. When the Indians saw her returning they evidently suspected her mission and was poured in a terrific volley. She said it seemed that the whole 400 fired at once, and the bullets knocked dust into her eyes so she could not see… she gained the fort without a hurt.” (2)

To the modern reader, running a 60-yard dash does not sound like much of an accomplishment. But do so carrying 25 pounds of gunpowder slightly uphill and across the sights of a couple of hundred rifles, and with the fate of family and friend riding on your effort, is truly the stuff of legends. For anyone wishing to revisit the scene of her heroic dash, it would have been from the northwest corner of the Horne’s building to about the middle of the field near the Fort Henry historical marker in the 1000 block of Main Street.

With the new supply of powder, the spirits of the defenders must have gone up considerably. There were other good points to ponder as well. It was becoming clear that the threat of 1500 additional Indians and a cannon was a ruse. The defenders had thrown back three assaults and realized they were up to the task. Their defensive firepower was aided by a generous number of public muskets that were stored at the fort. Together with many extra hands to load them they acted as what is termed in modern military parlance as a “force multiplier” for the frontiersmen. For the rest of the day the enemy had to be content with taking pot shots at anyone inside the fort foolish enough to give them a target.

The Indians were particularly incensed about the swivel gun. What frustrated them the most was that they had no way to “talk back” to the enemy. Sometime during the second day, some enterprising sort among them decided to try his hand at homemade artillery. A suitable looking log was found and them split and hollowed out. Some chain from the blacksmith’s shop was wrapped around it to contain the blast. For ammunition some cannonballs were taken from the boat that had appeared at the start of the fight. The rangers tried to warn the Indians not to attempt to fire it, but they would hear none of it. Shortly after dark it was drug toward walls of the fort. When a firebrand was put to the breach, the would-be cannon exploded. The only damage it caused was to anyone foolish enough to stand around it. Those inside the fort added insult to injury by jeering at them for the attempt.

About ten o’clock that night they made a fourth attempt to storm, but to no better purpose than the former. (2)

After having four assaults turned and beaten back, the British and Indians decided on a different approach. The little blockhouse to the south had been particularly troublesome.

If they could get next to the walls of the fort the swivel gun could not fire nor could any one at the loopholes in the walls. Only a few rifles in the blockhouses could be brought to bear on them. The problem was that whenever they got to the south or east walls of the fort, they came under fire from the blockhouse. To eliminate this threat an Indian was to try to get as close as possible to the little outpost. He was then to toss a firebrand into the window to set the redoubt afire.

Waiting to greet him was Ebenezer Zane’s slave Daddy Sam. Like Betsy Wheat, John Tate and others, Sam was another of those lesser- known heros of the second siege. Sam was said to have originally come from Guinea. He was described as short and muscular with coal-black skin. An aside, there were three other Black American participants at the battle. The others were Sam’s wife Kate, the unnamed slave who escaped from the enemy, and “Aunt” Rachel Johnson. Aunt Rachel was one of those rare characters who was most probably at both sieges of Fort Henry. She also appears in other Wheeling histories as Black Rachel. On the death of her owner, Yates Conwell, she was freed and given some property near Fish Creek. Later she operated a small dress shop.

As the Indian made his final approach to the kitchen window, he began to whirl the firebrand to make it burst into flame. Seeing this Daddy Sam immediately swung his big musket into action. He fired at the Indian incendiary at probably no more than the distance of a good-sized dinner table. His target was outlined for a brief second in the muzzle flash, and then the arson-minded Indian vanished in the darkness. While Sam was not sure if his shot was fatal, the Indian’s howl let him know he clearly had scored a hit. More importantly, the firebrand lay smoking harmlessly outside of the blockhouse.

The defenders had noticed that the assaults of the second night were not nearly as spirited as the first. As the sun rose on the third day of the siege it was becoming clear that the Indians were beginning to drift away, Fort Henry had held. One Indian decided that if they could not take the fort he would at least have the last word. Sure that he was out of rifle range, from the island, he bent over and raised his breachclout and showed those in the fort his bare rump in a final act of defiance. Deciding he could now afford to waste a shot, Ebenezer Zane fired and drilled the ill-mannered invader in the seat of learning. Zane could take comfort not only in having the last word, but for giving the Indian a lesson in manners he was not likely soon to forget. Sometime around noon a relief force of 40 men under Col. David Williamson appeared. The Indians host broke up into small raiding parties and continued to terrorize the countryside.

A week later word came from Fort Pitt that the British were calling back the rangers from further offensive operations. Fort Henry was the last time British and Patriot militia would view each other across the sights of a rifle, giving the Second Siege of Fort Henry a legitimate claim to the title “The Last Battle of the American Revolution.”

Author’s Note: The battle was reconstructed from the eyewitness accounts of Lydia Boggs Shepherd, Stephen Burkham, Rachel Johnson, and Ebenezer Zane, along with the remembrances of Ebenezer Clark.