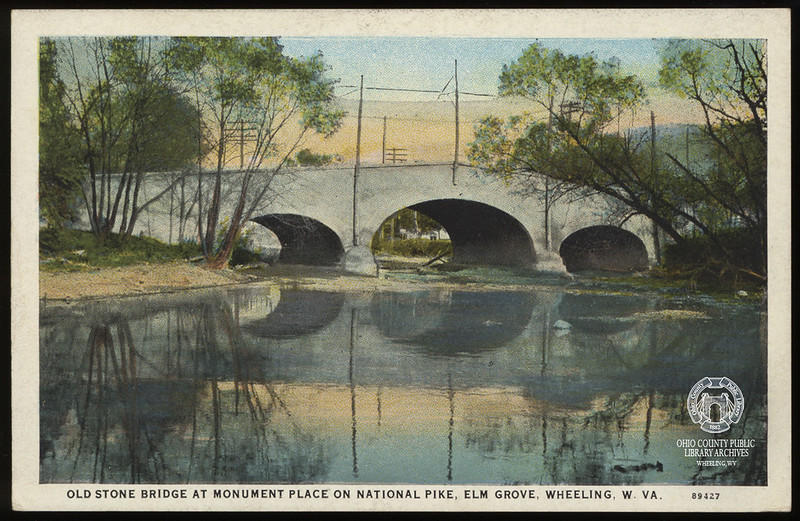

The Elm Grove Stone Arch Bridge has become part of many Wheeling residents’ daily routines, connecting commuters to downtown and providing access to the main Elm Grove strip. Hundreds of cars pass over the Stone Arch Bridge every day, but very few realize that they are experiencing a piece of history—the bridge is over 200 years old and is the oldest surviving bridge in the state of West Virginia.1

Building Bridges

Decades older than the state of West Virginia itself, the Elm Grove Stone Arch Bridge was built in 1817 over the Wheeling Creek as the National Road (today’s Route 40) made its way to Wheeling.2 It was one of two stone bridges that were built in Ohio County for the National Road, the other being the “S-bridge” in Triadelphia—named for its distinctive path shape but has since been removed.3

Construction of the National Road was one of the first federal infrastructure projects in the fledgling United States. As the responsible party, the U.S. Government commissioned Moses Shepherd to construct both the Elm Grove and Triadelphia bridges on the new road.4 Moses Shepherd, and his wife Lydia Boggs Shepherd, owned the Shepherd Hall plantation in the current Elm Grove area, a mere stone’s throw from the location of the Elm Grove bridge. While Moses Shepherd was the person commissioned to build the bridge, it certainly wasn’t a one-person job and there is no indication that he, himself, performed the physical labor. While unverified, it is possible that Shepherd paid a Charles Wallace $1,500 to build the bridge.5 The Shepherds also owned enslaved people, so it is possible that they were also forced to help with construction.6

The bridge itself has three elliptical arches, is built out of limestone, and “preserves early American engineering and masonry craftsmanship.”7 However, the bridge looks quite a bit different today than it did when it was newly completed in 1817. In 1931, the original parapets on the sides were removed and replaced with sidewalks and guardrails as automobiles increasingly replaced horse and buggies. A few decades later, in the 1950s, the bridge was sprayed with gunite—a concrete blend—for stability purposes. Unfortunately, the gunite covered up the iconic stone look of the bridge.8 However, it can still be seen in places where the gunite has cracked and fallen into the creek below.

The Shepherds and the Myth of National Road

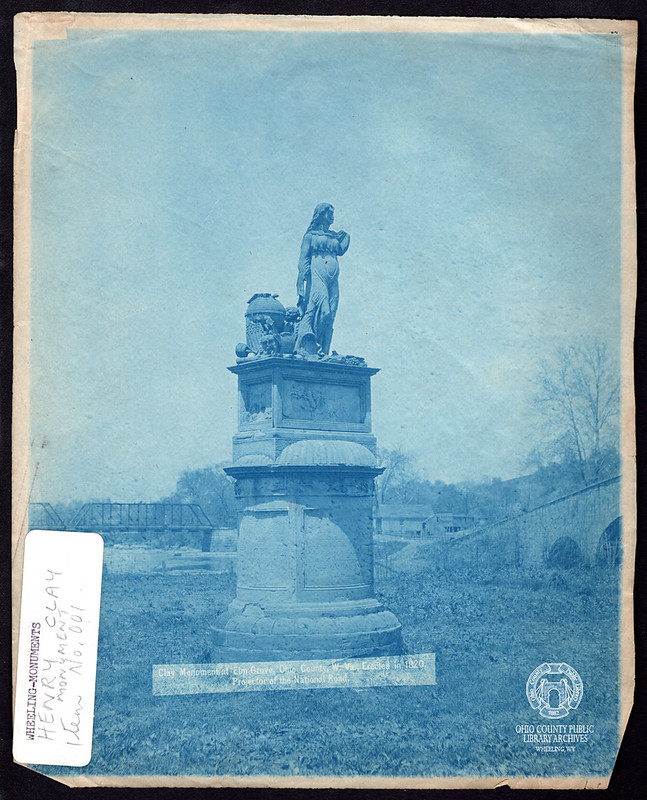

For over two centuries, a myth has persisted about Moses and Lydia Boggs Shepherd’s role in the National Road construction. During the planning of the road in the early 1800s, there were discussions about whether the route should go more north and cross the Ohio River at Wellsburg or further south at Wheeling. It was widely believed that the Shepherds—Lydia, in particular—used their friendship with Congressman Henry Clay to influence the decision for the road to go through Wheeling, right past the Shepherd’s plantation.

However, while this narrative can still be found in many history books and stories of the area, it is not all together truthful. The decision to route through Wheeling was made without the Shepherd’s influence, because it was already determined to be the most advantageous route. The water on the Ohio River near Wheeling was more navigable than further north near Wellsburg. Moses Shepherd did get the road shifted slightly, extending it about 200 yards so that it would pass closer to his front door, but he paid for the alteration personally.9

Even though it wasn’t the Shepherd’s friendship with Henry Clay that moved the road, they still put up a monument to Clay in their yard, right next to the bridge. Thus, the plantation got its nickname “Monument Place,” and the bridge was also alternatively known as the “Monument Place Bridge.” While the nickname still pops up now and then, the monument itself crumbled long ago in the 1930s.10

Throughout the more than two hundred years that the Elm Grove Stone Arch Bridge has stood in Wheeling, it has served an important thoroughfare. It saw the growth of the Elm Grove community and the advancement of technologies from buggies to cars. Even as much of its thru-traffic got redirected once I-470 and I-70 were built in the mid-20th century, it still retains its local popularity. As expected, older infrastructure requires maintenance to keep it structurally sound and safe for all travelers, which is why the West Virginia Division of Highways plans to close the bridge in 2022 to ensure it can withstand another two centuries.

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 Michael J. Pauley, “National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form,” West Virginia Division of Culture and History, State of West Virginia, July 1981, accessed May 25, 2021, http://www.wvculture.org/shpo/nr/pdf/ohio/81000606.pdf.

2 Ibid.

3 Becky Calwell, “Elm Grove Stone Arch Bridge,” e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia, September 18, 2017, accessed May 25, 2021, https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/2389.

4 Pauley, “National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form.”

5 Jack Maynard and Barbara Maynard, Elm Grove: A History in Pictures, Wheeling: Creative Impressions Studio, 1999.

6 George Fetherling, Wheeling: A Brief History, (Wheeling: Polyhedron Learning Media, Inc, 2008), 23.

7 Pauley, “National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form.”

8 Ibid.

9 Dan Bonenberger, “Myths & Landmarks of West Virginia’s National Road,” Wheeling Heritage.

10 Pauley, “National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form.”