This weekend, Wheeling will come together as a community to celebrate Juneteenth National Independence Day. Juneteenth, a word created from the combination of June and nineteenth, represents the day (June 19, 1865) when the last members of the enslaved population were freed by executive decree upholding the Emancipation Proclamation. While the Emancipation Proclamation was issued two years prior, its enforcement relied on the advancement of the Union Army. The surrender by confederate general Robert E. Lee two months prior had effectively ended the Civil War, but it took union soldiers until June 19 to retake control of the southern states and ensure that enslaved individuals were freed. Galveston, Texas was the last stop. Thus, Juneteenth is observed annually as a day of both independence and remembrance.

Since 2019, the Wheeling Area Juneteenth Celebration has started with a ceremony held at Market Plaza. By celebrating at Market Plaza, just steps away from the former location of Wheeling’s slave auction block, our community both bears witness to history while also celebrating Black liberation.

At the Borders

Prior to 1863, Wheeling was located in the northern panhandle of Virginia. The Commonwealth of Virginia was the largest exporter of enslaved persons,1 and while the western portion of Virginia (present-day West Virginia) had fewer plantations than the eastern region, Wheeling was not immune to the cruelty of the slave trade. Sitting at the intersection of the National Road and the Ohio River, Wheeling was at the crossroads of an efficient route to move enslaved persons to larger markets and plantations in points further south. Being “sold down the river” was an event so grave it entered common speech as a phrase that indicated a profound betrayal,2 the Ohio River was also a symbol of hope. Slavery was illegal in Ohio, and crossing the river was one of the first steps freedom-seekers in this area would often undertake.

Wheeling’s Second Ward Market House

“The auction block was on the west side of the upper end of the market about where the city scales are now located. It was a wooden movable platform about two and a half feet high and six feet square approached by some three or four steps.”

-John Salisbury Cochran, from his book, Bonnie Belmont. Published in 1907.3

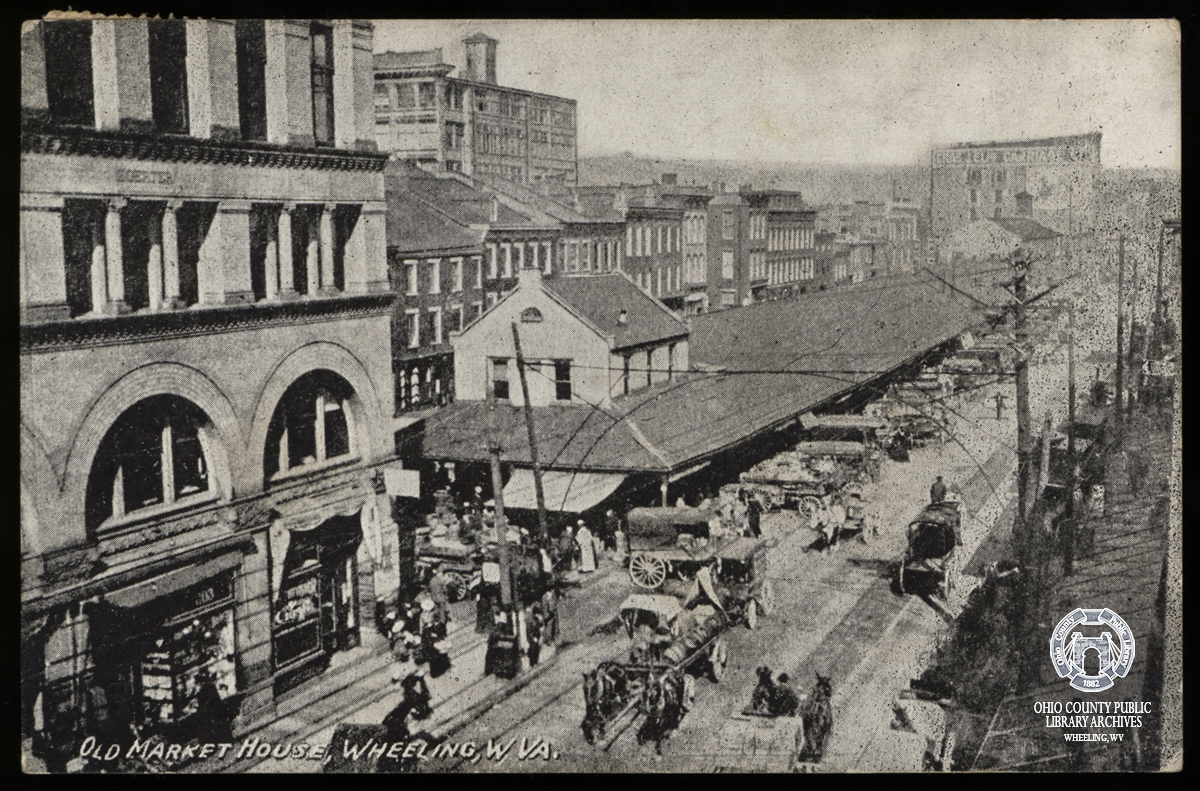

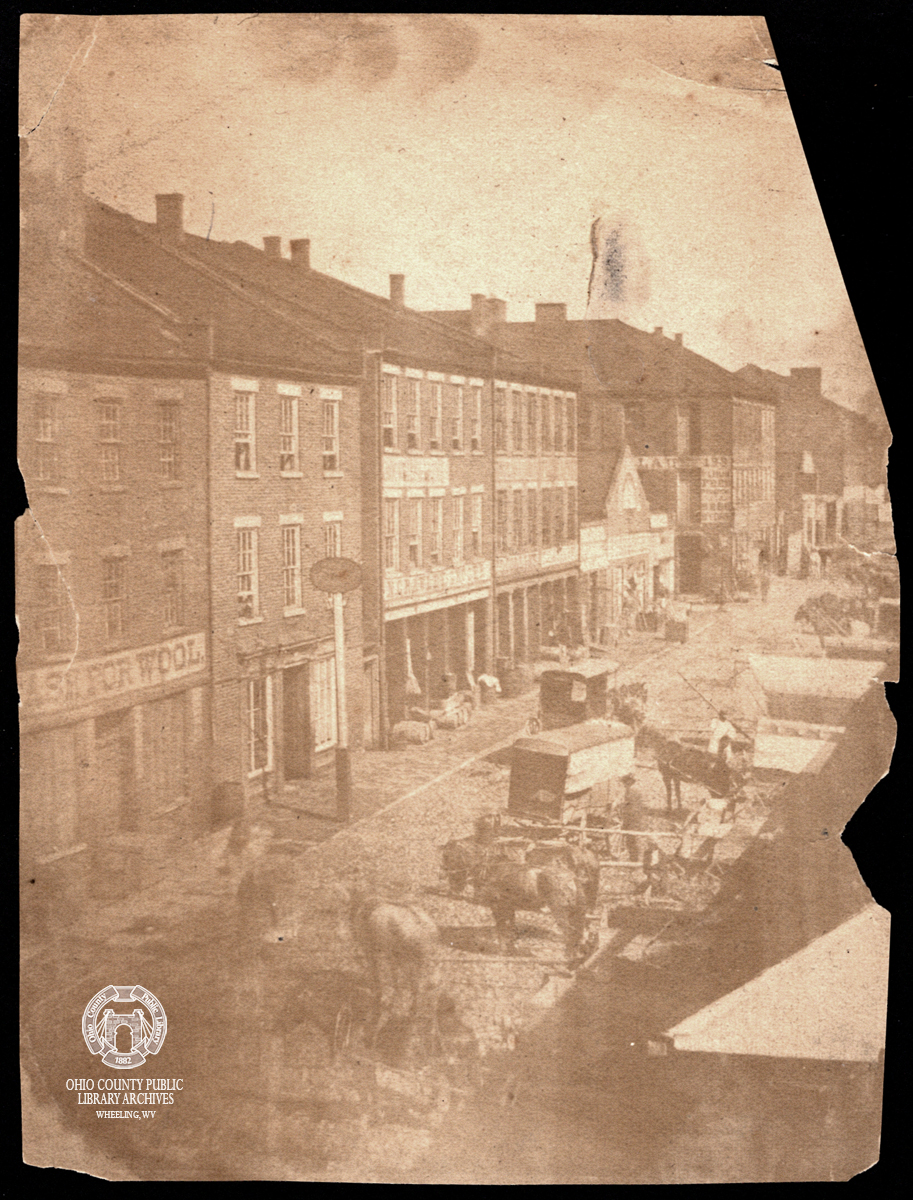

The Second Ward Market house at the corner of 10th and Market streets was the site of one of the earliest markets in Wheeling. In addition to farmers from the area coming to sell their produce, slave auctions were held at the north end of the market. Few descriptions4 of the site exist in the historic record, but multiple sources affirm that auctions did occur at this site. Local Quakers included the horrors they witnessed at the Market House in their abolitionist literature, and according to Cochran’s account, would occasionally participate in auctions with the intent to immediately free those they were successful in purchasing.5

The Second Ward Market was also a site of resistance. Wheeling’s location at the extreme borders of the state— hundreds of feet from the Ohio River meant that freedom was visible. Aided by a network of Free Black people, Quakers, and other abolitionists local to Belmont County, enslaved people who found themselves in Wheeling had a fighting chance to escape bondage. For some, freedom could be bought, but for others, freedom could also be sought via escape routes out of town and across the river.

Agents of Freedom

In one former conductor’s recollections6 of the Wheeling Market House, he identified a few Black men by name who were instrumental in helping enslaved people take their first steps towards freedom. According to Ellis B. Steele’s oral history, Richard Naylor and Samuel Cooper, two free men living in Ohio, chose the location for one of the first stations between Martins Ferry and Burlington. Samuel Cooper’s son, Henry also helped with their efforts. For a time, these three men worked together with other abolitionists to ensure a steady movement of people away from locations where slavery and slave patrols were rampant.

After years of service at this station, suspicions began to mount about Henry Cooper, and so in order to preserve his freedom, he had to flee to Canada. Soon after his departure, his father, Samuel was likewise suspected and also had to “seek a more desirable home” in Canada. Another free man, Thomas Pointer succeeded them so that the station was allowed to remain open.

While it appears that the Coopers and Pointer were primarily focused on helping people once they had left Wheeling, Richard Naylor’s job often took him right to the doorstep of the Second Ward Market. An example of brilliant misdirection, Naylor would hang around the market and feign drunkenness while also quietly passing information to the people being held there on how to escape. Eventually, suspicions mounted against him as well, and he had to depart to Canada for his own safety. Steele noted that when Naylor left, the “business on the road was exceedingly dull” indicating just how important Richard Naylor’s direct efforts were.

Wheeling’s Market House Post-Emancipation

The location of the Second Ward Market House continued to be a hub of activity in the City of Wheeling, throughout the 19th and into the 20th century. Until 1911, the Market House was used for vendors and farmers on the street level, and city and county meeting halls on the second level.

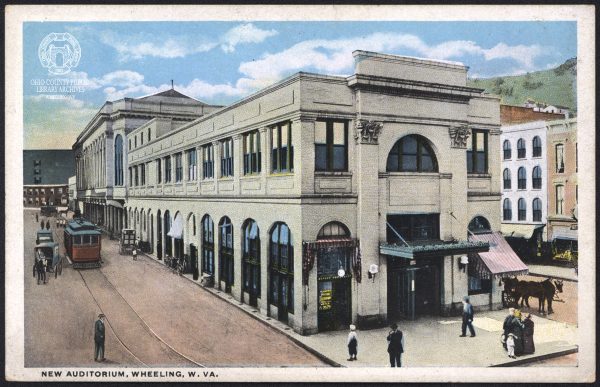

In 1911, the Second Ward Market House was razed, and construction began on the Market Auditorium. The Market Auditorium served much of the same purpose, providing spaces for vendors to sell their products, but also housed entertainment spaces, including a roller rink and performance space for live music. It is also important to note that while slavery was no longer practiced, these, and most other public spaces in the city, were deeply segregated. The Market Auditorium Skating Rink, though located adjacent to the heart of Wheeling’s Black business district, only allowed non-white community members the opportunity to skate for 30 minutes on certain evenings. Throughout the 20th century, the area including and surrounding the Market Auditorium was a complex site that both celebrated Black achievement and segregated members of the community from one another. To learn more about this section of Wheeling during the Jim Crow era, check out History In Their Own Words: Memories from the Black Community.

In 1964, The Market Auditorium, like many of the buildings around it, was demolished as part of Urban Renewal – a racially-motivated planning initiative that provided funds for cities to identify and clear the people and buildings in areas determined to be “blighted.” Demolished in the name of “progress” many of the vacant lots still standing empty today date back to this movement.

Market Plaza and Juneteenth Today

Today, Market Plaza continues to illustrate a complicated history. A piece of concrete stands out, with a sign explaining the history of the slave auction block that once stood there. Turn in either direction, and you will see Black-owned businesses contributing to the revitalization of the City of Wheeling.

Like Juneteenth, Market Plaza stands at the intersection of remembrance and celebration. This weekend, it is important to understand the significant and painful history that gave way to the celebration of liberation. For more information about this weekend’s slate of events, visit WheelingJuneteenth.com.

• Kate Wietor is currently studying Architectural History and Historic Preservation at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia. She spent one glorious year in Wheeling serving as the 2021-22 AmeriCorps member at Wheeling Heritage. Since moving back to Virginia, she’s still looking for an antique store that rivals Sibs.

• Betsy Sweeny is the director of heritage programming at Wheeling Heritage. She is an architectural historian, yoga teacher and dog mom to her rescue dog Marshall.

References

1 John Zaborney , “Slave Sales.” In Encyclopedia Virginia. 2021, August 10. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/slave-sales.

2 Lakshmi Gandhi, “What does ‘Sold Down the River’ Really Mean? The Answer Isn’t Pretty.” Code Switch [NPR] 2014, January 27. https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2014/01/27/265421504/what-does-sold-down-the-river-really-mean-the-answer-isnt-pretty

3 John Salisbury Cochran, Bonnie Belmont: A Historical Romance of the Days of Slavery and the Civil War. 1907. Press of Wheeling News Lithograph Company. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Bonnie_Belmont/ovVEAQAAMAAJ?hl=en

4 Seán Duffy, “Wheeling 20th Man: 250 Years of Race Relations in the Northernmost Southern City of the Southernmost Northern State.” Archiving Wheeling. 2020, June 23.http://www.archivingwheeling.org/blog/wheelings-20th-man-250-years-of-race-relations-in-the-northernmost-southern-city-of-the-southernmost-northern-state

5 John Salisbury Cochran.

6 Ibid.

7 A.T. McKelvey, “Recollections of Ellis B. Steele.” Centennial History of Belmont County, Ohio 1903. Appears in Lillie: Black life in Martins Ferry in the 1920s and 1930s. by Jacob C. Williams, Sr., 1991