Note: This is a fictional tale. Rich Knoblich, WV storyteller and a regular winner of the Liar Contest at the annual Vandalia Gathering hosted by the WV Dept. of Arts and Culture, likes to add some drama, mystery and fun to his fables. It’s been said that some of the best lies are ones that are weaved with a thread of truth, which is exactly how Knoblich designs his short stories. Can you spot the truth in this tale?

A mundane parking lot southeast of the Wesbanco Arena belies its true nature. The lot lies on the northern bank of the confluence of Wheeling Creek with the Ohio River, a plot of land that holds a legitimate claim to being the most historic site in the Ohio Valley. Yet some say it holds another title, too — haunting ground. It starts with the legend of a skull placed upon a pole marking the land as a site of revenge, an event which has served as a prelude to centuries of paranormal occurrences in the immediate vicinity.

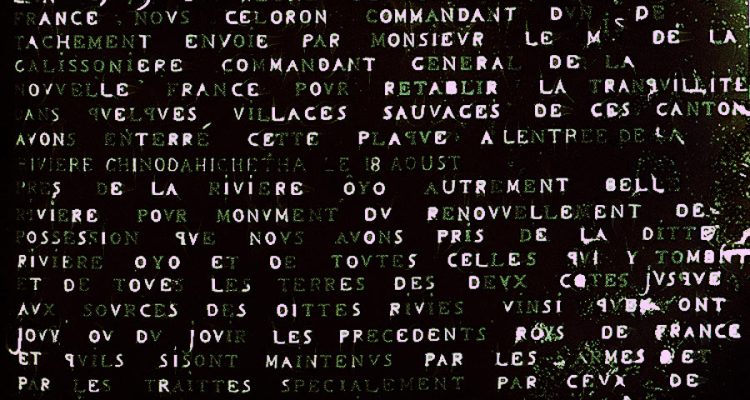

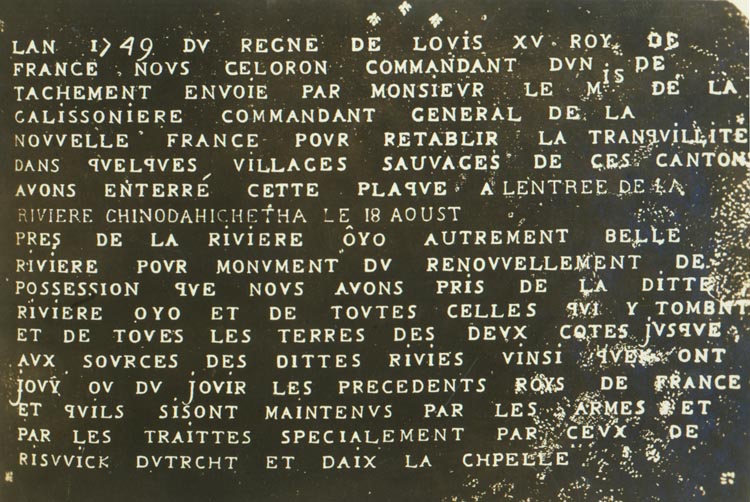

Céloron’s Plaque

The Native Americans found the Ohio easy to ford here with good hunting on the island and the surrounding floodplain. Early fur-trading French frontiersmen were attracted to Belle Riviere, the French translation for ‘beautiful river,’ for the same reasons.

When British traders started to infiltrate Belle Riviere, the French government felt the need to solidify ITS earlier land claims. Therefore, in 1749 the Governor General of New France ordered Pierre Joseph Céloron de Blainville, stationed in Montreal, to reassert French dominance. Céloron’s troops attached metal notices to trees and buried lead plates at major streams emptying into the Ohio River. Two of the six historic lead plates, measuring 11 x 7.5 inches each, have been recovered. Translated:

In the year 1749, of the reign of Louis the 15th, King of

France, we Céloron, commander of a detachment sent by

Monsieur the Marquis de la Galissoniere, Governor General of

New France, to reestablish tranquility in some Indian villages of

these cantons, have buried this Plate of Lead at the confluence

of the Ohio and the Chadakoin, this 29th day of July, near the

river Ohio, otherwise Belle Riviere, as a monument of the renewal

of the possession we have taken of the said river Ohio

and of all those which empty into it, and of all the lands on

both sides as far as the sources of the said rivers, as enjoyed

or ought to have been enjoyed by the kings of France preceding

and as they have there maintained themselves by arms and by

treaties, especially those of Ryswick, Utrecht and Aix-la-Chapelle.

From the upper windows of the Main Street Bank’s offices in the Wagner Building, employees have an overview of the lot to the north. Veteran staffers initiate new employees on dense foggy mornings. They will bring them to the windows looking toward the north and whisper, “Do you see it? Watch. There in the swirling mist. See them? The ghostly crew of Céloron’s expedition is burying something to lay claim for France.” Whispering, “Telle est la vie.” [French for Such is life.]

Steamboat Washington

By 1788 came the short-lived Fort Randolph, built after Fort Fincastle (renamed Fort Henry for Patrick Henry, 1774-1784). By the early fall of 1815 boat builders repurposed its timbers for the construction of the first steamboat in Wheeling. The Washington became the first of over 100 steamboats constructed in Wheeling. It possessed a new flat bottom design made to ride high and maneuver in the often shallow river waters of the west. The Washington launched on May 12, 1816.

Although the steamboat hull worked successfully in shallow water, a major misfortune befell the Washington. In July of 1816 near Marietta, Ohio, the steamboat’s boiler burst, a common occurrence of early boilers. The explosion killed or maimed several individuals. Captain Shreve was seriously injured and blown into the river. But, he survived to navigate the river later for many years.

However, people along the river gradually received news of the explosion. Although Shreve survived, primitive communications being word of mouth, they mistakenly thought he died. Valley folklore tells of the vaguely seen image of Captain Shreve reportedly piloting phantom steamboats gliding silently along the steaming Ohio. The river lore became entrenched. People still claim to see the specter steering riverboats forewarning of a catastrophe about to strike near the confluence of river and creek.

Once constructed the Washington’s builders waited for the arrival of engine parts sent over the mountains from Brownsville, Pa. It would take awhile since the National Road did not reach Wheeling until 1818. Henry M. Shreve put this time to good use. Shreve’s carpenters constructed a covered bridge over Wheeling Creek for easier access to the farmland south of Wheeling and Ritchietown.

Main Street Stone Arch Bridge

After many years the wooden covered bridge became the victim of an ice jam. A second bridge lasted a few decades until it collapsed.

Construction of the current bridge began under the supervision of Dominick Carey, a 48-year-old engineer of Paige, Carey, and Co. based in Cleveland. His company had expertise in designing durable structures like train trestles and railroad tunnels. Designed with a single span of 159 feet, the stone arch allowed clearance for ice jams and debris washed down by flood waters. The entire bridge spans 232 feet in length. This stone arch bridge is the longest of its kind in the region and, at 123 years old, it still supports modern traffic loads. But like other undertakings touching this historic ground the bridge manifested its share of tragedy.

During Carey’s bridge supervision he resided at the Hotel Windsor. On Wednesday evening, Jan. 13, 1892, he discussed with a friend in the lobby the unexpected death of Benjamin Fisher, a prominent businessman. While talking about this sudden loss with Mr. Gil Brown, Dominic Carey casually shrugged off the peculiar twist in fate occasionally handed one: “Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die,” he commented to his friend.

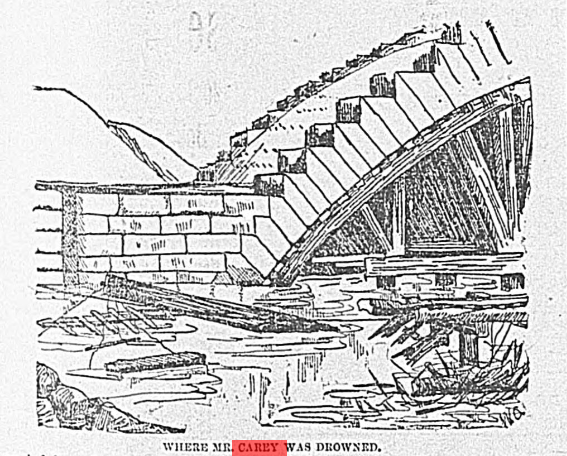

The next day, Thursday, Jan.14, at 9:45 a.m., the bizarre occurred. After talking with Mr. Lathrop, his office associate, Mr. Carey left to conduct a bridge inspection. The frigid, muddy waters of Wheeling Creek rushed swiftly below the site.

The creek ran high causing concerns for the safety of the workers. Mr. Carey began his inspection of the bridge’s support structure to assess its soundness. A tram had been built to carry heavy sandstone blocks across the stream for placement on the opposite side of the construction site. As Carey walked out onto the wooden beams, a loud crack exploded. The sound drew the attention of the construction crew. To their horror they witnessed the tramway collapse with Dominick Carey falling into the muddy rushing waters. The tram with its heavy stone load fell onto the exact spot where he was last seen.

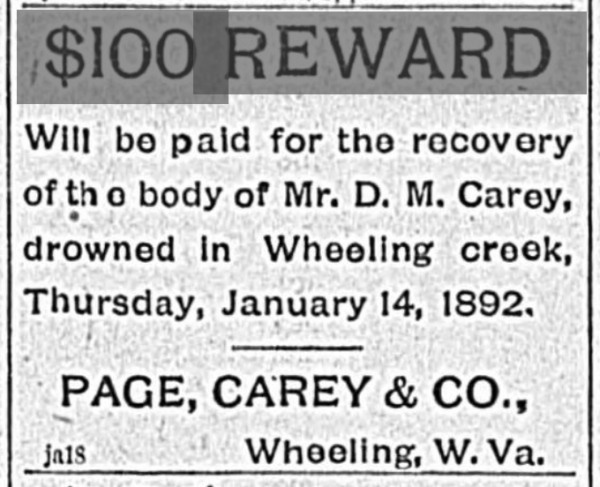

Searchers never recovered his body even after newspapers ran a $100 reward notice on the front pages in hopes that fishermen or riverboat crews might recover his body in a downstream eddy. The Cleveland company which employed him sent two divers as soon as they heard of the tragedy. The divers found no trace of him. Mr. Dominick Carey, left behind a wife and three young children, the oldest child being only 8 years old.

The terror of drowning is a basic fear. Perhaps this tragedy made an impact on the local psyche. People driving over the Main Street Stone Arch Bridge during wintry mornings report witnessing a strangely attired man on the bridge. He wears a bowler hat fashionable in the late 1800s. Peering over the stone sidewalls, he studies the structure to ascertain its safety for the pedestrians and vehicles crossing Wheeling Creek. It is claimed to be the ghost of Dominick Carey and the phantom supervisor continues inspections to insure the bridge’s safety. Built 123 years ago, the bridge, in spite of Mr Carey’s untimely demise, still stands with the watchful eye of the guardian contractor working to ensure everybody’s safety.

The Flat Iron Building

Bordering the northern edge of this lot, and adding to its phantasmic mystique, sits the 1896 Flat Iron Building. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, this structure comes under different names (Riverside Iron Works Building, Karnell Building) with a variety of businesses occupying it over the years. This structure gets its common name from the triangular shape of the building. When city streets are laid out, topography or other impediments can cause platting of an odd triangular shaped lot. But the land is still valuable enough for building. The “flat iron” name, for the wedge-shaped design of such buildings, derives from the pointy cast-iron clothes irons once used.

Originally three stories, a fourth floor was added at about 1907. Corinthian pilasters border the windows with decorative Romanesque brick arches. Decades later this fourth floor contained rundown apartments which made them affordable to young reporters and other poorly paid professionals. To reach the upper level one entered the first floor which once housed the Stark Artificial Limb Company.

An acquaintance once lived there for a short time. He likes to relate this story:

“I was out drinking late one night and had a tough time lining up the key to unlock the door. I weaved unsteadily with my key scratching the paint around the keyhole, unable to insert it. Then I felt a hand grasping mine and guiding the key into the lock, turning, and opening the entrance door. Mind you, I didn’t see a hand; I only felt one. Once inside I had to make my way down a narrow aisle to the stairway in the back leading to the apartments. Bordering this aisle were display stands with wooden artificial limbs for the Stark Artificial Limb Company, which occupied the first floor. As I staggered my way to the stairs, I kept tripping. When I finally got to the bottom stair, I looked back. Everywhere I tripped lay an artificial wooden leg toes up on the floor. I made it up to my room in record time.

The next day I quit my job, found a new apartment, and got employment in the food service industry. Over the years I worked my way up to head manager. I figured after that spooky night, if I was going to be tripped by legs, they’d better be attached to tables and chairs.”

The historic sequence of this lot reveals a skull, a historic plaque buried by long-gone French frontiersmen, a fort, a ghostly riverboat pilot, a phantom bridge inspector, and wooden limbs tripping you. As for the parking lot itself, still embedded railroad tracks of a bygone era curve across it and then across Main Street under a corrugated metal door of the Boury Building where the rails disappear into its environs. But that’s a mystery for another time.