Peter Junkersfeld grew up in New York City, one of America’s largest melting pots of people with a plethora of persuasions, nationalities, religions, races, and sexual orientations.

David Miller, a man born in 1951, was raised here in Wheeling, a city with a mass of heterosexual Christians as well as a very crowded closet full of people who were labeled different because they didn’t fit the exact same description.

Big city. Small city. Acceptance. Refusal. Welcoming. Unwelcoming.

The Wheeling area was well known as a region where the men worked hard in the mill, and the ladies stayed home with the children. It was the norm, and it was expected, and Miller found the same expectations after relocating to Morgantown in the mid-1970s.

“I even got married. I tried,” he said. “I really did, but we knew it wasn’t right. She knew, and I knew, and that’s why we made the decision that it would be far better to be divorced and love each other than to be living together and pretending that it was something it was not.”

Her name was Gayla Vandenbosch, a woman Miller dated for two years prior to proposing the peer-pressure-pushed nuptials.

“I believe we were the first couple to do our own divorce,” Miller explained. “She came as my witness, and it was over in 10 minutes. She’s a phenomenal woman, and I still have my ex-wife as a very close friend.”

Miller then moved to the Washington, D.C., area and met Junkersfeld two years later in a gay bar. Peter was the bartender, and David was the patron.

“Since Peter was raised in New York City, he has always had a completely different perspective than anyone in West Virginia could possibly have about the gay community,” he said. “His familiarity of New York became my familiarity of New York, and it was a lot of the same in the D.C. area probably because there were so many kinds of people from all over the world. That has helped me, and I have been a gay activist ever since then.”

While Miller may have cared about what other people thought, Junkersfeld does not recall a moment when he’s harbored inhibitions about his sexual orientation.

“My perspective on all of this is so different than most people here in the Wheeling area because he and I come from totally different backgrounds. I’ve always been out there, and I’ve never had to worry about being out there. My attitude was that if you don’t like it, you can kiss my you-know-what,” he said with a broad smile. “I feel more pain for David than I do for myself because I’ve never had to experience what he has.

“The reason I don’t have the problems with being gay is because I was very, very young when my mother knew, and while growing up in New York, I was exposed to the whole world, and it was kind of normal,” Junkersfeld said. “It’s a very different atmosphere because it wasn’t difficult to be the person I was born to be.”

Friends Were Dying

It was only a couple of years after their union when a disease labeled AIDS surfaced in the United States. It was an unknown illness to most, and, according to national news reports, when it appeared at the time, it was limited to homosexuals because thousands of men were dying across the country. The public ignorance led to unjust assumptions.

“Although I feel I’ve always been an activist, I really got active because of the AIDs epidemic and how people were turning their backs on gay people,” Miller said. “The gay community had to start taking care of itself because no one else wanted anything to do with it.

“After Peter and I met, we were mixing with the general population. We weren’t just sticking with the people in the gay community because we wanted to just put ourselves out there. But as far as our friends and the people at the gay bar where Peter once worked, well, half of those people are now dead. People were dying left and right in Washington, D.C., at that time.”

The majority of people, though, didn’t seem to care, Miller recalled, but it did lead to constant discrimination by those in both the private and public sectors.

“We had a friend who was diagnosed with AIDs, and he started living with us so we could take care of him,” Junkersfeld recalled. “The first people who showed up at our home after we called in the emergency were officers from the homicide unit. Homicide. I couldn’t believe that.”

“Oh, discrimination occurred,” Miller said, “and it was rampant after the AIDs epidemic began, and it went all the way down to funding. It was a truth I didn’t want to believe, but that just pushed me to be more of an activist than I was already.

“For the majority of my life I have worked with individuals with cognitive disabilities, and we really studied how to get people into the community. That work allowed me to learn how to effectively accomplish community organizing so I could help those individuals get included into their communities,” Miller explained. “I used those same skills to fight for the gay community.”

Home for Mom and Dad

Soon after America’s homeland was attacked by 19 terrorists who hijacked four planes on Sept. 11, 2001, David and Peter decided to move to the Elm Grove neighborhood of Wheeling.

“Peter has always loved West Virginia because of our visits, but this time we were moving from the Capitol Hill area because my mom and dad were getting older, so we came here to provide them support,” Miller explained. “They were with us until about two-and-a-half years ago. We lost them within three months of each other, and then Peter was diagnosed with lung cancer.

“That was a very tough time for us — a very tough time. It didn’t make sense,” he said. “But it happened.”

What started as lung cancer had led to groin cancer and a brain tumor, and Peter and David found themselves seeking treatments for Junkersfeld outside the city of Wheeling. That’s when Miller realized that, while he had not encountered issues involved with his sexual orientation previously, he did on this day.

“Since we moved to Wheeling, we’ve always been out there. We’ve never felt as if we had to be hidden away,” he said. “And, as far as discrimination is concerned, I can tell you that there have only been a couple of incidents that have taken place since we moved here, including the time when Peter was seeking treatment for his cancer and a person kicked a chair across the room, and I was told to go sit in the corner.

“It didn’t hit me at the time. My initial thought was that he was just a cranky old bastard, to be honest, but then on the way home I really started thinking about it. Was that discrimination? I think it was,” he continued. “What happens, though, is that you become hardened to it, and that makes you not realize it all of the time when discrimination is taking place. It forces you back, though, into a form of hiding,”

But in October 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court refused an appeal on same-sex marriage, so such unions became legal in West Virginia. Although Peter was very ill, this couple became the second gay marriage to take place in Ohio County.

“The best part was that our friends really came together to make it all happen. We had Neely’s chicken and T.J.’s cole slaw, we had five different kinds of cakes from the bakery at Centre Market, I made the mac and cheese, a friend brought one of the best cheese plates I’d ever seen, and other friends did the decorations and the lights outside,” Miller said. “It was all done by our community.”

“It makes me want to cry when I think about it because our friends made it such a special time for us,” Junkersfeld said. “And there were people from this community who drove me up to Pittsburgh when I was very sick, and they did that every single day,” he said. “Can you imagine that? It was breathtaking for me.

“And today I am cancer free,” he reported. “I just had a very big doctor’s appointment, and that’s what they told me, so everything is good right now.”

Four Out of Seven Necessary

David has publicly spoken several times during meetings staged by City Council and the Wheeling Human Rights Commission since returning home, but his support for the city’s gay community often fell on deaf ears.

“I’ve always believed that a lot of it had to do with the power that was in existence then,” Junkersfeld said. “They weren’t big on it because I believe they didn’t want to rock the boat. But see, the way I was raised, I believed that sometimes, when it’s really important to the people living here, you have to rock the boat sometimes.

“I’ve never experienced discrimination here in Wheeling. I know it happens, and I know it’s happened to David, but not to me,” he said. “But I do know there are a lot of people here who are scared, and that’s why they have remained hidden.”

But earlier this year members of the Human Rights Commission voted in favor of sending a Resolution to council and Mayor Glenn Elliott that strongly encouraged the several elected individuals to develop a non-discrimination ordinance that included members of the city’s LGBT community.

Following a pair of public work sessions involving City Council and the Human Rights Commission, a public meeting that attracted more than 300 residents, a first reading of such an all-inclusive ordinance that includes veterans and Caucasian males and females, the second and final reading and a vote on the proposed legislation is scheduled to take place Tuesday at 5:30 p.m. in City Council Chambers.

“And during that process is when I encountered discrimination for the first time here in Wheeling,” Miller said. “It was when Mr. Chris Hamm stood up there. I found it repulsive when he said he didn’t understand why the ordinance was needed. I wanted to tell him right then that it was because he’s not gay.

“I was alive when women got equal treatment and when those with disabilities were finally included, so this is another step now that we have realized that people have been discriminated against,” he explained. “There was a need to add to that list, and it is my hope that, if it passes, it sends a strong message to the lawmakers from around the state.”

Although West Virginia State Code does not have a similar statute on the books for the Mountain State, 22 states plus Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico do have laws that outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation, and it is also illegal in 20 states plus D.C. and Puerto Rico to discriminate based on gender identity or expression.

“The ordinance in Wheeling can pass, and it will be a very important step for the city of Wheeling, but we all know it’s not something that will take away the prejudice. That’s the case, too, with all forms of discrimination,” Junkersfeld insisted. “Now, I can say that I was really surprised at the reaction at the public meeting at the end of November at the White Palace. I honestly did not expect that.

“That was a pleasant surprise, and it showed me that the overall attitude has changed around here a great deal,” he added. “It made me proud to live here in Wheeling.”

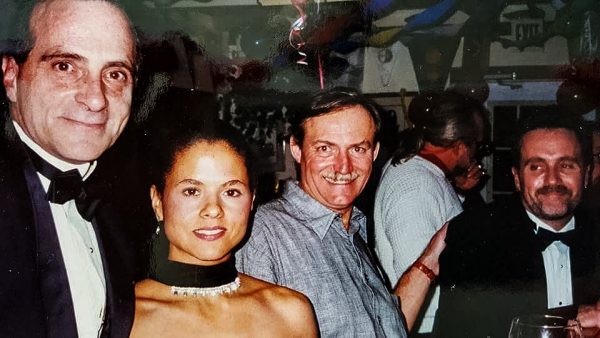

(Cover photo by Rebecca Kiger; photos provided by David Miller)