As the AmeriCorps member for Wheeling National Heritage Area, I have been doing research on the history and architecture of the Warwood neighborhood since September. In February, an employee at the Wheeling Water Works treatment plant gave me a full tour of the filtration plant and pumping station. Since the filtration plant is scheduled for demolition this summer, I wanted to document as much of the building as possible. I began my research by taking over one hundred photographs of the filtration plant; I was surprised how much information I found on its history.

Photos courtesy of Wheeling National Heritage Area

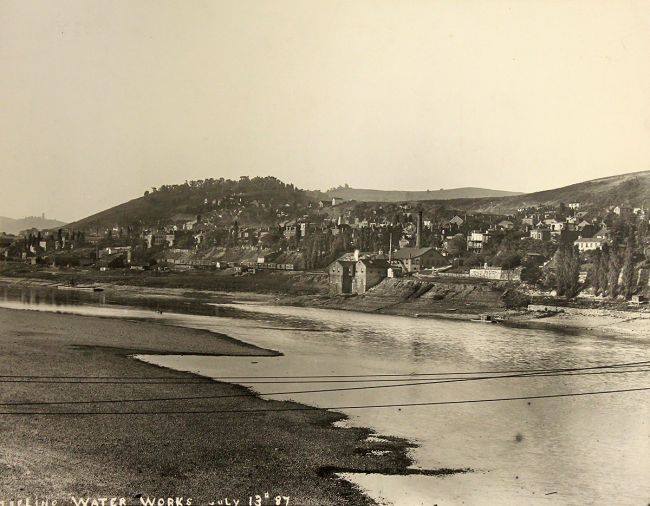

Nearly a century before this filtration plant was erected, the first Wheeling Waterworks plant was built downtown on 8th Street, near the Ohio River, in 1834. Frederick Faris designed the second plant on River Road, between Warwood and North Wheeling, in 1892. In 1924, five years after the town of Warwood was annexed into Wheeling, the city relocated the waterworks to the neighborhood. By relocating the facilities, city officials sought to further integrate Warwood into Wheeling and acquire a higher quality of water; a Wheeling News-Register article from 1935 notes that Warwood was, at one time, listed as a town with the purest water in the United States.

J.N. Chester Engineers, the firm who designed the filtration plant (and pumping station), was founded in 1910 in Pittsburgh; now known today as Chester Engineers, they are also known for designing architecturally exceptional municipal buildings, some of which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places (including the Omohundro Water Filtration Complex District in Nashville and the Oakland Water Treatment Pumphouse in Maryland).

Like the pumping station next door and the Warwood School across the street, the filtration plant is a grand display of fine Art Deco design. The movement was most popular from the mid-1920s through the early 1940s, when artists and architects sought to break from the past with geometric motifs, low-relief decorative panels, and vertical projections. At the filtration plant, the low relief panels play on vertical lines to emphasize its four-story height. Its octagonal-shaped foyer boasts a tall, domed entrance with marble floors, oak paneling, and geometric patterns. On the façade, the engineers played with basic shapes through the triangular pediment on the tower, the pink half-circle over the entablature, and the wrought iron transom light. The front entrance alludes to the preceding Neo-Classical movement with classical columns and pilasters, while the glass-block windows around the entire complex are a dead giveaway for any Art Deco building.

The filtration plant is scheduled for demolition this year, as early as May. As a self-proclaimed preservationist, I understand that not every building can be saved. This is not the first time, nor will it be the last, that I’ve seen a building become obsolete because of its incompatibility with modern technology. Nonetheless, if we can’t save old buildings, we might as well learn as much about them as we can.

Photos courtesy of Christina Rieth